This article was originally posted on GunMag Warehouse here.

BLUF: There exists a gap between military and commercial vernacular, and this is the bridge. If the military is going to make up names for rifle types and the commercial market is going to use them to name their products… fine. But there has to be (or should be) a standard, on the commercial side, and among private end-users. There must be order. That order might best be attained by using nomenclature inspired by intended use and extant systems.

Below you’ll find eight primary types of rifles…plus one more.

Rifle Typing: What’s in a Name?

- INSPIRED Background

- Rifle Typing

- AR-15 Variants

- General Purpose Rifle (GPR)

- Special Purpose Rifle (SPR)

- Close Quarters Rifle (CQR)

- Personal Defense Weapons (PDW)

- AR-308 Variants

- Battle Rifle (BR)

- Designated Marksman Rifle (DMR)

- Semi-Automatic Sniper System (SASS)

- Compact Semi-Automatic Sniper System (CSASS)

- Exceptional Purpose Rifle (XPR)

INSPIRED: Rifle Types

The C⁴ (Configuration Classification Categories & Criteria) System, for Regular Guys.

We have a terminology/lingo problem in the 2A market and surrounding community. There are multiple dialects of the same language spoken, with much lost in translation. Certain phrases mean different things to different people. Some of it is institutionalized. Lots of it is commercialized.

All of it is confusing.

The problem I’m talking about is how certain rifle configurations (of the AR platform in particular) are colloquially referred to.

Military naming conventions can be inconsistent themselves, though at least those rifles have an M or Mk/”Mark” number used to specifically set each one apart. This inconsistency carries over into the commercial side of the firearms industry and is compounded by myriad companies cherry-picking product names based on “.mil” naming conventions.

This is a marketing tactic; they are implying their product is like or comparable to what the military is using in a similar or identical capacity. But they do this with complete disregard for the doctrine(s) that spawned the nomenclature.

And this is done inconsistently as well — there is no “civilian” standard for the terminology applied. This results in commercial end-users, i.e. the “regular guys” in the market, reflecting this inconsistency throwing names and labels around to describe or label their weapon configuration(s). These regular guys, who usually don’t know any better, are typically civilian members of the 2A community (but may also be armed professionals). The result is chaos.

The intended purpose of this article is to bring order to that chaos. It will seek to clarify the terminology used for various types of guns by narrowing it down to configuration categories with unique criteria. The goal is to assist the regular guy in navigating and understanding the market options available to them and hopefully optimize their rifle configuration toward its intended use.

Such a configuration will be, in most cases, based upon what that person sees utilized by professionals that carry rifles for a living, including those specialized for similar purposes or capabilities the regular guy may desire. Some gun buyers might copy such weapons as closely as possible, but that won’t always be the case. Usually, the responsible citizen prospective gun buyer is in a position to afford better commercial options than what most professional organizations (that don’t allow self-supplied weapons) will provide or authorize for use.

So, be forewarned. If you’re a pedantic “cloner” that can recite the build spec sheet of a rifle and any variations of it used by the US military, this isn’t for you — though you guys do generate some baller gun porn! Your historical knowledge is as useful as it is interesting and therefore respected, but the naming convention outlined below will not jibe with rigidly dogmatic adherence to military-based nomenclature.

Leave all that at the door before you proceed, or just leave. There’s your first warning.

I will repeat this several times throughout the article to anchor purpose and practicality. The primary intention here is to streamline the communication process to a more simplified format.

Secondarily it is to normalize such standardized categories via circulation and dissemination and then hopefully a subsequent awareness within our community.

The equation is simple:

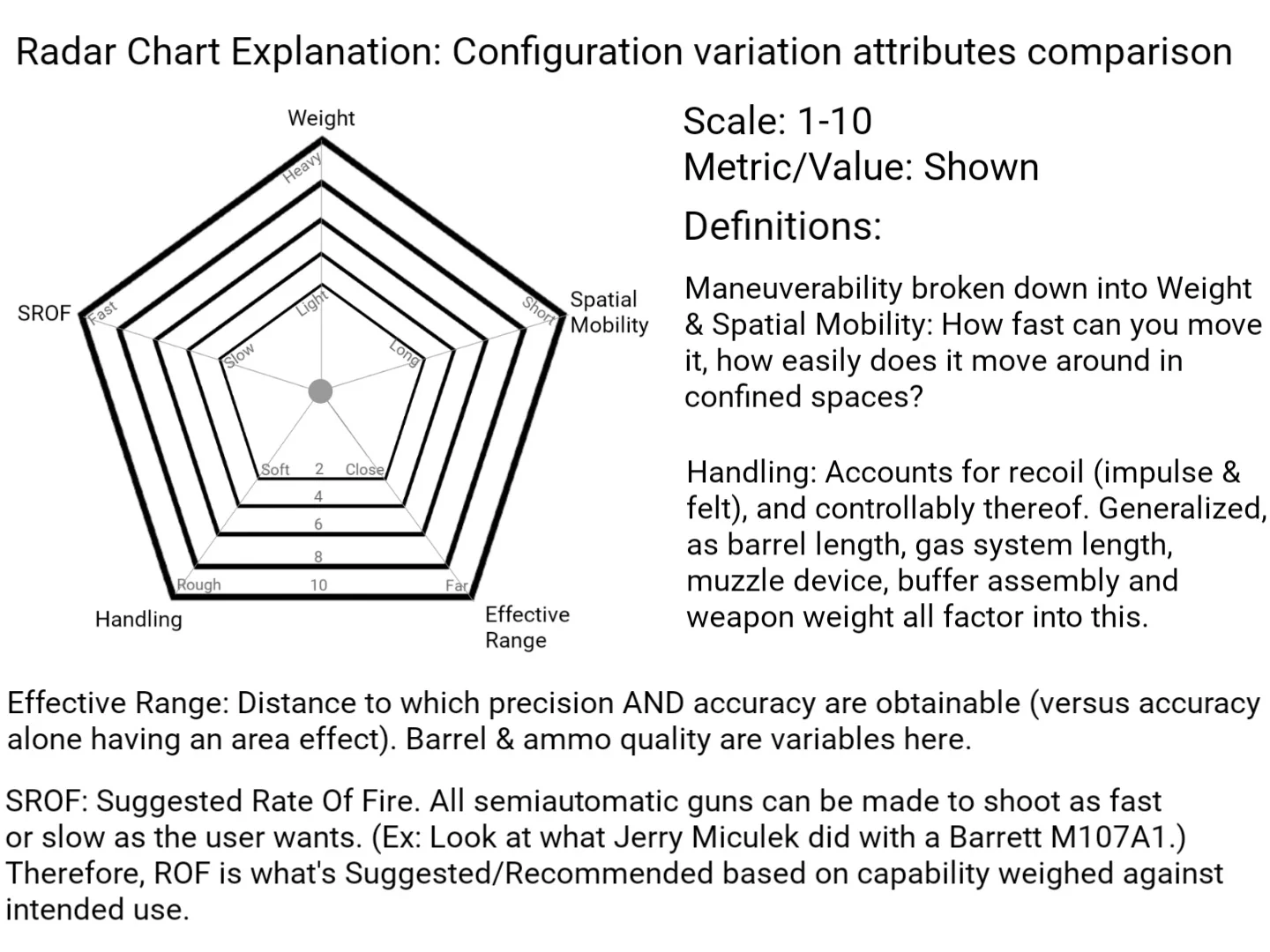

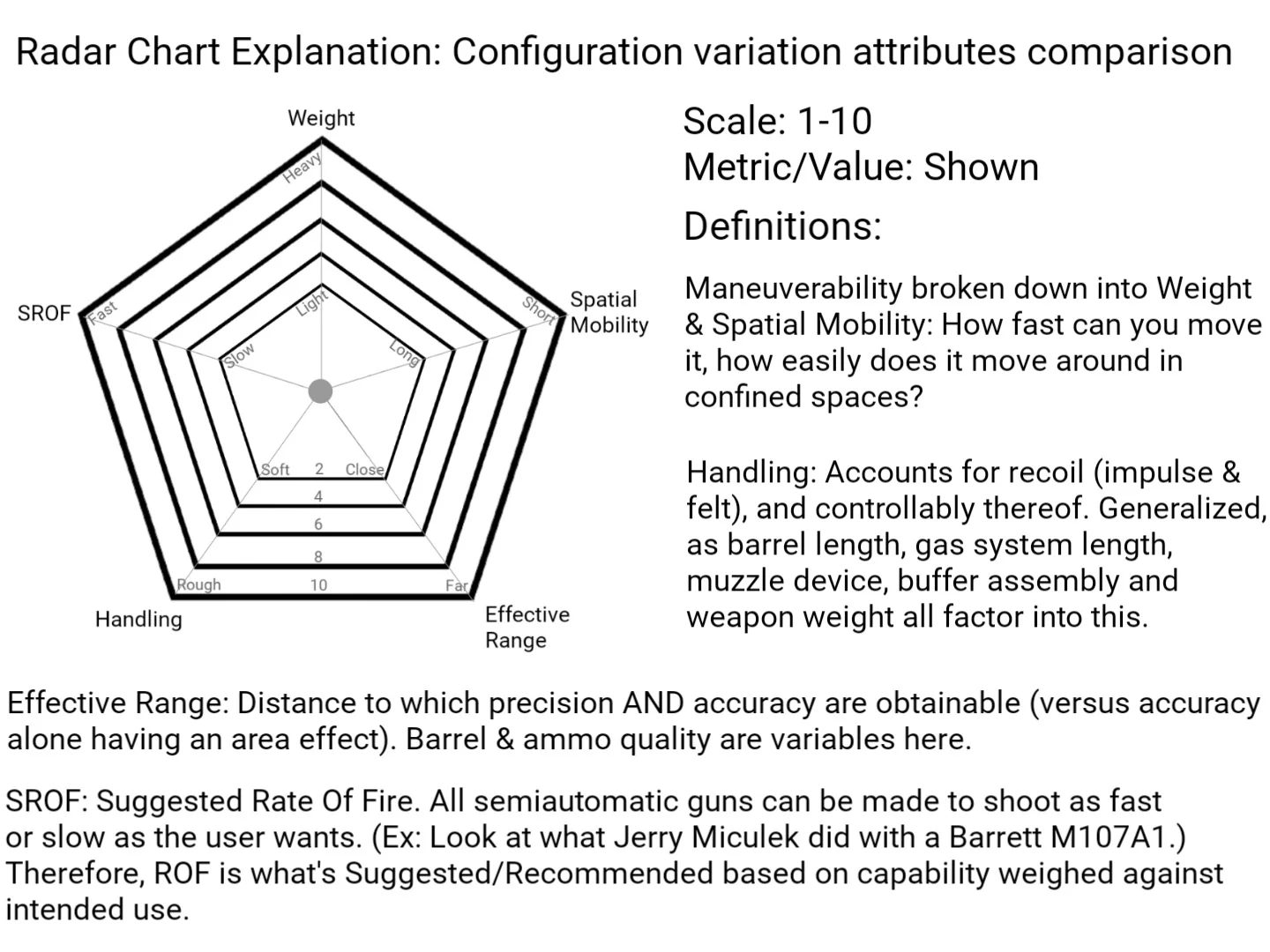

Configuration weighed against intended use, then named after the nearest applicable military example(s), if available.

Rifle Typing In Action

This is how it works.

• Look at the configuration.

• Evaluate which job or task the configuration is optimized for.

• Name or describe the category of all likewise configurations after the most colloquially recognized examples of .mil rifles configured and used for the same purposes (where such terminology exists) or

• Describe it based on its characteristics comparable to the nearest adjacent .mil configuration.

Example: “Battle Rifle”, “DMR” (Designated Marksman Rifle), “SPR” (Special Purpose Rifle), and others are all existing terminology. “GPR” is a truncation of the phrase “general-purpose rifle”, commonly used to describe rifles of such use in layman’s terms.

Why? Because the mil stuff is what everyone in the commercial market sees. They say, “I want something like that,” and the industry knows this.

So then the industry says, “Let’s name our stuff after that so people buy it when they want to get something like that.”

This is why the slides you see in each category section use as many .mil examples as possible; they’re what the industry/commercial market and customers thereof copy or are “inspired” by. Hence the prefix in the article title.

I’ve developed this naming convention based on my personal experience. This is how I’ve been referring to and navigating configurations and the inconsistent labels applied to them for years. However, before codifying it and presenting it here I sought input and review from a wide array of knowledgeable individuals.

Allow me to present a DISCLAIMER: This is not a guide to translating military doctrine naming conventions. But since the industry uses doctrine terminology to market their products, doctrine terminology will be used to describe the industry’s products by evaluating them as a whole/by the sum of their parts. This is not how the military does things; this is how I navigate the way the military, and the industry that follows it, does things.

That said, there will be people that don’t like this. They will outright reject the idea. My answer to them is tough shit. If you are part of that crowd, stop reading now and avoid unnecessary angst and drama.

The inherent inconsistency of the military and related doctrinal terminology creep into the commercial industry is what necessitates my system. The advantages that a streamlined and simplified colloquial system will provide to the commercial market are many and manifest.

If you are extremely orthodox in your approach to this subject and your ass is so chapped that you’re outraged or losing your mind, this is your stop. If you continue, you have no excuse to be upset. Fair warning has been issued, three times.

But if you’re that regular guy, and you’ve ever sat there wondering what the difference between an SPR and a DMR is, come along, this was written for you.

AR-15 Variants

We begin with the standard frame AR-15 variants in 5.56 & .300BLK, starting with the most commonly carried configuration in private and professional hands: the General Purpose Rifle.

BLUF

- GPR: The jack of all trades, does every job acceptably enough to be the mainstay configuration. Balances maneuverability and effective range.

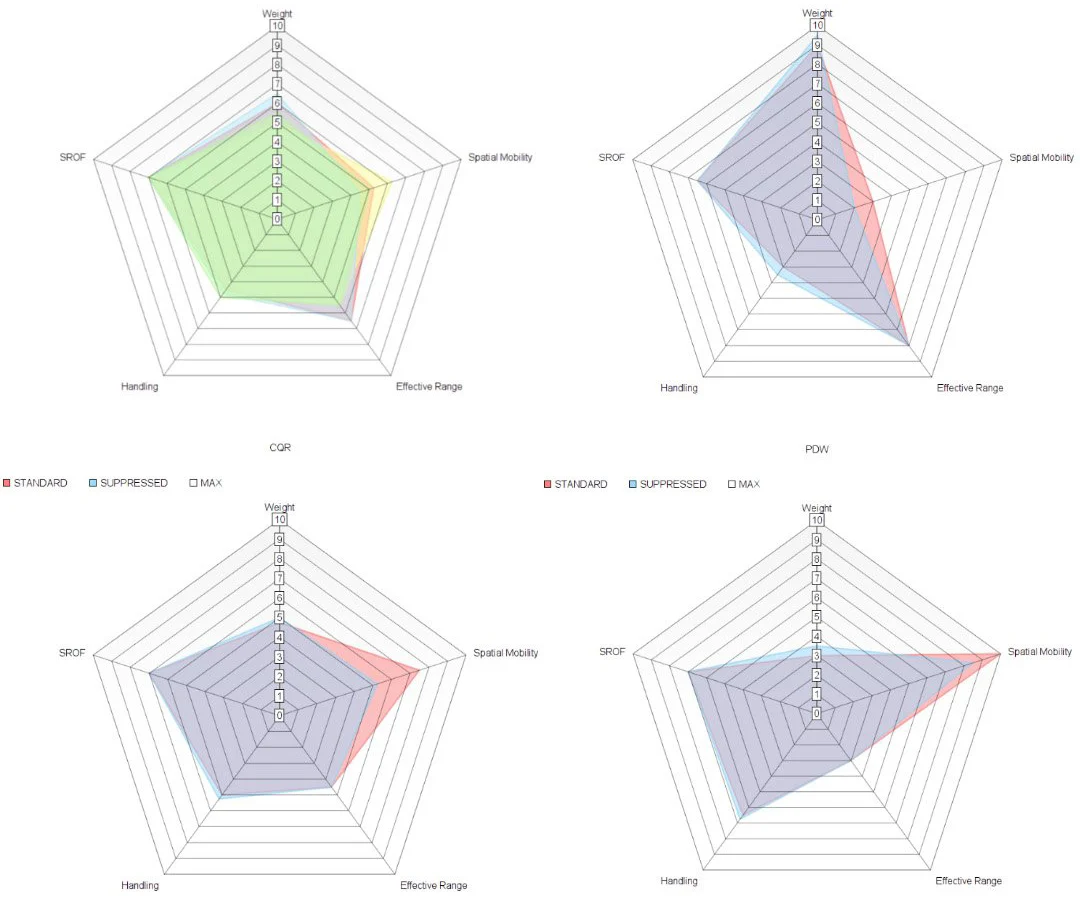

- CQR: Specialized for close to mid-range engagements, sacrifices effective range for maneuverability and/or signature reduction.

- PDW: Sacrifices effective range for concealment, signature reduction, and lethal maneuverability in extreme close-quarters engagements.

- SPR: Accurized for distanced precision fire at max effective range, in exchange for maneuverability. Retains commonality/standardization at the squad level.

GPR: General Purpose Rifle

The standard configuration category. The jack of all trades. The meta. Not unlike the M4A1, nearly everyone has one of these (or they ought to), and they can all do a little bit of everything.

They can reach out past 500 pretty well, but the longer dedicated configurations will do that better. They can handle close range and interior work just fine but aren’t as maneuverable as the shorter dedicated configurations. This is particularly true once you add a suppressor, which we’ll touch on later.

For the guy that’s on the fence about dedicated configurations and is more comfortable with something that can handle all tasks within a reasonable performance margin, the GPR is where it’s at.

A GPR is a weapon in which you’ve sacrificed a balance of some effective range for some maneuverability, and some maneuverability for effective range. The GPR is also suitable for someone who wants a training rifle they can cross state lines with, This allows travel across the country to training courses without having to worry about National Firearms Act (NFA) legality concerns.

It covers all the bases good enough to not really leave you wanting, especially if a pinned muzzle device doesn’t strike your fancy.

Q: “Why is called General Purpose Rifle instead of General Purpose Carbine, since the barrel lengths are all in carbine territory?”

A: Honestly, it’s interchangeable, but on paper, it’s still considered a rifle in black and white, anchored in the cartridge it’s chambered for, whereas carbine can refer to something in rifle or pistol caliber.

At the end of the day, the Pistol Caliber Carbines (PCCs) are just giant handguns with no greater terminal ballistic performance in their more common short barrel form. They offer no appreciable gains in terminal performance with longer barrels but do suffer the size and weight penalty of a rifle caliber weapon.

The combination of those two things in a weapon with pistol terminal performance is of arguable merit at best. These aren’t submachine guns (SMGs) with a select-fire option we’re talking about. I contend that PDWs do the PCCs job, but better, as far as go-to and backpack guns go.

Q: “Why not call it Recce Rifle?”

A: Because first and foremost, that term is mostly just dumb wannabe cool guy lingo. Secondly, the definition of “Recce Rifle” changes based on who you ask. If you ask Navy SOF guys, it’s an ~M4 sized rifle with glass as opposed to their Mk. 18s and HK416 SBRs. If you ask Army SOF guys, it’s basically a Battle Rifle in carbine form with glass on top (aka DMR, more on this below).

This actually serves as a case in point. The configuration was never consistent, but the purpose was.

You have to understand that “Recce Rifle” came about in a time before today’s technology existed. The “it can do everything good enough” version of the AR-15 or M4 with an LPVO that bottomed out at 1x and comparable to a red dot, and a free-floated rail that increased precision capability just wasn’t a thing at the time. So the “Recce Rifle” filled a capability gap between the short barrel stuff and the longer barrel accurized stuff. It could still push out accurately and precisely enough for the AO the guys using them found themselves in, but it was shorter for greater maneuverability.

But the most important reason “Recce Rifle” is no more is because…damn near everyone now has what we would once have called a Recce Rifle in the common form of the GPR. This is the increasingly ubiquitous carbine equipped with an LPVO in the 1-6/8x/10x range, but not used for actual recce purposes; more so because carbines equipped with LPVOs are currently the technological standard.

So if everyone is running around with a “Recce Rifle”, then nobody has a Recce Rifle. They just have a general-purpose rifle capable of a wide variety of tasks. Therefore the most important reason we didn’t go with the term Recce Rifle is that “recce” isn’t reflected in a configuration anymore. It’s just one task among several that one can perform with a GPR if needed.

With a wide variety of optics and barrel lengths to make combinations of, weighed against the capability and performance of those combinations, the GPR covers the widest range of applications effectively and reliably enough to be the “do-all” configuration of the AR-15 platform. Thus, General Purpose. It is the “squad standard.”

20″ barreled M16-like configurations almost made it to this category, but we’ll cover why they weren’t later on.

SPR: Special Purpose Rifle

This configuration of the AR-15 platform is optimized for long-range precision to the extent of the maximum effective range of the 5.56x45mm round.

This applies especially to the heavier BTHP & TMK varieties, as testified by the sum of its components:

- a rifle length barrel to stretch the muzzle velocity and flatten the trajectory as the bullet flies farther out,

- a free-floated rail to maximize the precision capability at distance, and

- a magnified optic to facilitate PID at further distances.

Everything about this configuration category says “My rifle’s job is to be more capable of precision fire and at further distances than the rest of the squad, while still being standardized and able to fall in with them as needed.”

The guy that shows up with an SPR automatically becomes your Squad Designated Marksman. Hopefully, he’s good at that role, or at the very least switches rifles with someone in your gang who is.

Let me take a sec to talk about this “squad” I’ve referred to a few times now. Let’s be real here, most of the intended audience for this article has taken “SHTF” into consideration when it came to their armament, their training, and those of their friends. Don’t be embarrassed, we’ve all done it and it’s okay. Encouraged, even. This country was built on the backs of local riflemen.

I don’t care what flavor of SHTF you subscribe to preparing for, or if some smug douchebag out there wants to call you a LARPer for it, that’s beside the point. The country’s been on edge for a minute now anyway so nobody could really blame you for thinking about it.

You’re not alone, this is why the ammo and hardware coming from the industry has been extremely hard to find over the last year+.

So when I say squad, I mean your friends who’re the kind that would ask just, Who’s car we gonna take? You could merely be fireteam-sized, but for brevity, we’re using “squad” interchangeably. Let’s pretend you and your squad are smart and you’re all using or at least in possession of 5.56 AR platform rifles because that’s the CONUS King. So you’re all 4-8 of you using the same style rifle with the same ammo and the same mags and spare parts. You’re standardized.

The SPR is therefore a squad-level weapon (retains parts/mags/ammo/interface interchangeability with the rest of the squad) with a specialized purpose: precision, and precision at range especially, beyond the GPR’s capability. That the actual Mk. 12 SPR was never utilized as a “squad” weapon but more at the fireteam level among NSW personnel using it doesn’t matter; because it seamlessly integrates with the GPRs the rest of your squad is carrying.

We will therefore consider it a member of the same family at the squad level.

It does not however imply or denote a “Sniper” or “Sniper Rifle.” That’s a different configuration for a different task, and the Squad Designated Marksman is still in the stack/moving with and among the squad.

The name is derived from the aforementioned Mk. 12 Mod 0/Mod 1 SPR, which serves as the basis by which every likewise rifle configuration in private hands is informed. You see it in marketing from the industry where whole rifles and components are sold under the name, or in a suggestive “comparable to” sort of way implied between the configuration and the name (like the KAC SR-15 LPR).

You’ll also see it used colloquially in chatter amongst the 2A community: when someone says “my SPR,” they are referring to an accurized AR-15 firing 5.56 optimized for long-range precision.

The keyword there is optimized: there is a difference between what an Optimized, Dedicated, or Purpose-Built configuration can do, and what another configuration is capable of.

Q: “My GPR is capable of doing an SPR’s job. Does that make it an SPR?”

A: No doubt, but also no. An SPR is optimized for an SPR’s job, and a GPR is not. It’s really that simple: between the two, one of them is going to perform that task better than the other. A 16″ barreled GPR with an LPVO can do an SPR’s job to an extent, sure, but an actual SPR is more optimized for the task via its rifle length barrel. And I know there’s a Mod H SPR out there with a 16″ barrel, but is it really providing you that much more maneuverability over an 18″ barrel? Not really. In fact, the only reason most people on the commercial side stick with 16″ barrels is solely to avoid stepping into NFA or Pin & Weld territory.

An uninformed glance might lead one to think the M16-based SDMR is just a standard-issue M16A4 + ACOG being used by a Designated Marksman. But it’s not, and though that may very well have been done overseas during the GWOT these last twenty years, there’s more to it than that.

The M16-based SDMR might use a 4x ACOG like an M16A4 and have the same barrel length, but it also has a specialized free-floating rail and barrel that further enable it for that task. An M16A4 clone with glass wouldn’t qualify as an SPR because it’s not optimized for that task by virtue of the drop in handguard rail, so.

Moral of the story: if you’re gonna do it, optimize it for the task.

Outside of the Mk. 12 SPR itself inspiring so many imitation AR builds in the commercial sector, there is one other rifle in the SPR category that provided one of the most well-known examples of the configuration category. That is the AR-15 used by Travis Haley in the 2004 Battle of Najaf during his days as a contractor.

The “Turkey Shoot” video seen far and wide over the years throughout the community demonstrated a textbook example of the SPR configuration’s capability, as Haley was engaging targets some 700m away from a rooftop in an overwatch position against enemy combatants. This display of what the configuration was capable of inspired many to build a similarly capable SPR type configuration, myself included.

I suppose another way of remembering or looking at SPR in this context would be “Squad Precision Rifle”. That phrase effectively and clearly communicates the intended use of the configuration. Despite the concept and task of the Designated Marksman, I like this better than “SMR” for “Squad Marksman Rifle” because SMR is too easily confused with MSR or “Modern Sporting Rifle”.

The latter is defanged paper tiger nonsense some genius thought would soften up the firearm industry’s product offerings in the eyes of its political opponents. Spoiler alert: it didn’t, and it won’t, and it’s bullshit.

But I digress.

Your optic can be an LPVO, an HPVO, a Combat Optic, or (more commonly) any of those paired with an offset MRDS. The MRDS or 1x LPVO settings allow you to do your close work (especially since HPVOs aren’t conducive to this). The magnification allows you to take advantage of the accuracy and precision that free-floating rail and rifle-length barrel combinations are capable of.

While sacrificing even more maneuverability indoors for greater range and precision capability outdoors, the longer SPR isn’t all that bad: the boys have been doing MOUT & CQB with M16s for decades. Not ideal compared to a carbine, but doable.

Q: “If the SPR is for the Squad Designated Marksman, why isn’t it called DMR or Designated Marksman Rifle?”

A: Sometimes it is. But that complicates things. In simplifying the category classifications, “DMR” is reserved for large frame ARs with a similar purpose.

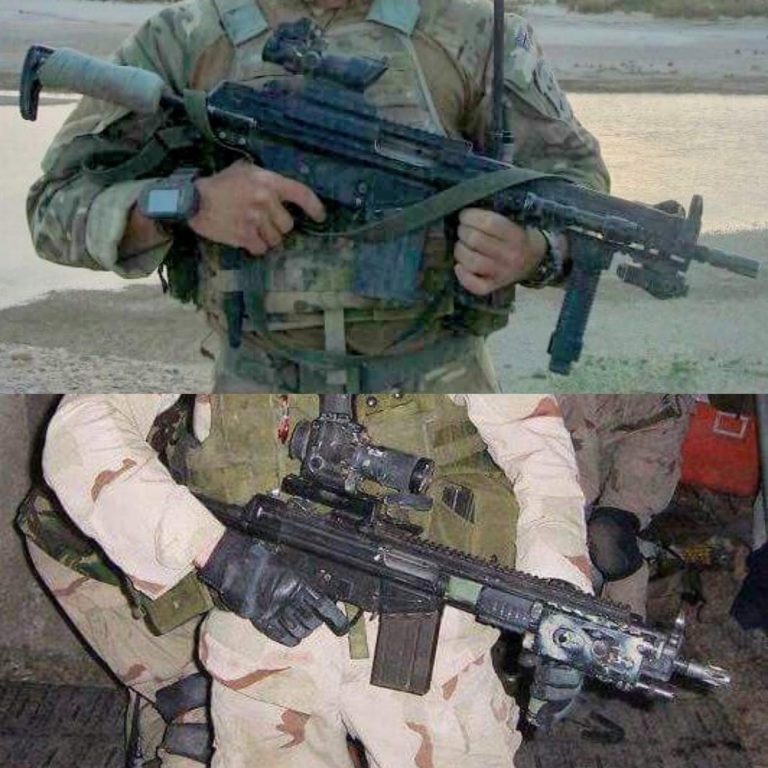

CQR: Close Quarters Rifle

The SBR configuration of an AR-15 that’s optimized for close quarters/indoor work.

Note that I didn’t use SBR for this (or any) category classification because all that means is “rifle with a barrel shorter than 16 inches,” and not every such rifle is optimized for the close-quarters task.

Q: “Why didn’t you just say CQBR like the Mk. 18?”

A: A couple of reasons. For one, the R in CQBR means Receiver and I didn’t want to introduce a new meaning for the same acronym.

Two, I liked that was able to get all the AR-15 platform configurations down to three-letter acronyms. Third, it’s pretty straightforward what it’s describing: a rifle configuration optimized for Close Quarters work.

There are two main reasons this configuration is optimal for Close Quarters:

Obviously, it’s very maneuverable compared to a rifle or standard carbine length weapon, due to its shorter length, which facilitates easier movement indoors.

That shorter length also facilitates signature reduction components without requiring you to exchange maneuverability in close quarters. A quieter weapon provides for better verbal communication among team members within a structure, which is a significant advantage. It also mitigates how badly the muzzle blast and concussion rattle your teeth — something that only gets worse as your barrel gets shorter.

Maneuverability is only half the equation.

When you add a suppressor to a CQR, what you end up with is a GPR-sized weapon that’s quieter than a GPR on its own. If you take a GPR and add a suppressor to it, you end up with a weapon the size of a rifle-length configuration. This cuts further into your maneuverability. And if you put a suppressor on a rifle length configuration, well… Close Quarters probably isn’t your first job, but your buddies will thank you for it regardless.

If “unsuppressed CQR indoors” was Plan A because you thought it was gonna be all fast and furious, you’re not wrong — but you’re not right either. A couple of shots in a shoot house with an unsuppressed CQR (or hell, any rifle for that matter, but especially a CQR) will tell you everything you need to know about why that’s a dumb plan. Even with electronic hearing protection.

It’s another trade-off. You’re going back to GPR maneuverability indoors in exchange for signature reduction within the same size envelope, and therefore better communication and reduced hearing damage.

I say “less hearing damage” rather than “no hearing damage” because 5.56 isn’t hearing safe even when it is suppressed. You should have electronic hearing protection anyway, but if you don’t — yeah the shit don’t sound like GoldenEye just because you’ve added a can.

Barrel lengths of 10.3″, 10.4″, and 10.5″ were the go-to for CQRs until very recently when the industry started trending toward 11.5″ barrels. The latter barrel provides increased systematic and ballistic performance benefits in a package where one extra inch doesn’t kill the maneuverability of the equation once the added length of a suppressor is factored in.

All in all, when CQB and Direct Action is your day job, the CQR is the configuration category you want.

As Uncle Pat used to say, the mission drives the gear train.

With the right ammo, barrel, and optic combination, you’re hot to trot out to 300m but wouldn’t have a problem out to 500 either.

It also helps that the shorter weapon makes for a lighter weapon, which is helpful when you start adding other accouterments to the rifle associated with CQB, especially more recently. As lights and lasers and offset MRDS are added for low light or no-light/night vision use, these things start to add up in weight.

I know that’s a thing for some people, and while there’s no reason you can’t or shouldn’t add all of those things (including suppressors) to GPRs or SPRs since they’re all complementary to general or special purpose applications, the weight and maneuverability remain something to be considered.

You’re probably wondering about yet shorter barrel ARs and why they weren’t included in this category. Well, we’re talking 5.56 as it’s our main fighting cartridge. It has all the commonality and industrial support you could ask for. In addition to CQR configurations not being hearing safe when suppressed, 10.3″ barrels are the absolute floor for terminal and ballistic performance.

You could shoot it from shorter barrels, but you’re losing so much in terms of range and terminal capability for the weight and size penalty of the weapon that that barrel length is best left for a different caliber entirely.

We move onto those next with the…

PDW: Personal Defense Weapon

The thing that separates PDWs from the CQR category is that they’re easier to conceal, and therefore readily deployable from concealment.

With the PDW style stock or an AR stock on a LAW Tactical folding adapter + a QD suppressor, that thing is bag ready.

That’s ultimately the point: easily concealable firepower that you only expect to use in close range to extremely close quarters and high maneuverability therein. This is usually for either executive or personal defense (duh), and consequently breaking contact and escaping either alone or with the person you’re protecting, be they family member (HD/Home Defense) or client (EP/Executive Protection).

Another suitable situation is one in which your infil and exfil need to be inconspicuous and you can’t appear to be carrying a firearm that you aren’t going to deploy and utilize until you’re right on top of your target anyway.

You could absolutely use them for CQB, and when suppressed they’ll be even quieter than a CQR in most cases when using subsonic ammo. You’ll also get back some of the maneuverability you gave up suppressing the CQR.

But as always, there’s a trade. If the SPR category covers the ARs configured with a dedicated long-range purpose in mind, the PDW is its exact opposite. It has all the maneuverability, speed, and concealment capability, but your range capability is reduced.

You can rule the roost inside, but if that fight goes outside, ehh…

The PDW can do range, but not a lot of it. Ideally, it should not be the first thing you grab if you reasonably expect to be engaging targets at distance. With supersonic ammo, you can hang out to 400m or so, but that’s it, and even then only after considerable hold and a nosedive of bullet drop.

We keep going back to that keyword of optimization. While the PDW can reach out some, it’s not optimized for it. That’s not what it’s there for.

Q: “Well, what if I just get a longer barrel to shoot .300BLK from?”

A: It’s not going to change the trajectory significantly enough to make it worth the weight penalty or the expense, nor will it increase the effective range. I don’t care what’s been accomplished competitively, comp rifles aren’t typically built for practical applications.

Stay focused.

The most important thing to keep in mind about .300BLK is that it’s not a replacement for 5.56. It was never meant to be, and it never will be. It is, however, a shoulder-fired 9mm replacement.

What .300BLK does do is allow you to use subsonic ammo and a suppressor to do an MP5’s job indoors just as quietly. You can then, with the simplicity of a magazine change, switch to supersonic ammo and do what no MP5 could reasonably be expected to do past 50m (let alone at four times that distance).

There are other advantages as well. It has the exact same manual of arms as 5.56 AR-15s and 1:1 parts compatibility with the exception of just one component: the barrel. That barrel ought to be short, well shorter than 10.3″ at least.

That’s what it was made for: .300BLK shines when it’s fired from a suppressed PDW-sized platform.

It will be a tad louder suppressed if you’re shooting supersonic ammo instead of subsonic ammo, but the lethality on top of the range capability you get from that supersonic ammo crushes what a 9mm PCC has to offer, while still suppressing and stabilizing better than most 5.56 ammo fired from the same barrel lengths.

At least an MP5 (a real one, I mean) has burst and full-auto functions to provide some extra utility, but in the commercial market at large, these are rare. The overwhelming majority of gun owners won’t be buying or feeding transferable full-auto rifles or SMGs, so I’m looking at this through the lens of what is readily, commercially accessible to the most amount of people in the market.

It also has an added benefit for LE agencies that use both AR/M4s and MP5s by allowing them to streamline their logistics and armory training needs. Instead of two wholly different sets of parts, it’s just one. The only thing different is the barrel; everything else is the same. That’s a significant potential logistic and financial advantage.

They also only need to send armorers to a single training course (for the AR-15 platform) versus two for that and the MP5. Whether they wanna replace their MP5s 1:1 with .300BLK PDW-sized weapons, or just buy new uppers to use with their existing AR/M4 lowers will depend on how much money they have to spend.

So if your task is:

- Backpack/break-contact gun,

- Home defense/executive protection, or

- In and out, smash and grab wetwork, then

The PDW configuration is the one to consider.

You’re not trying to hit that guy way over there, but you are giving yourself enough distance and maneuverability to be very lethal, very close, very quietly, and very quickly.

Now that we’ve cleared the standard frame configurations, we’ll step up to the large frame AR-308 varieties.

AR-308 (AR-10) Variants

BLUF

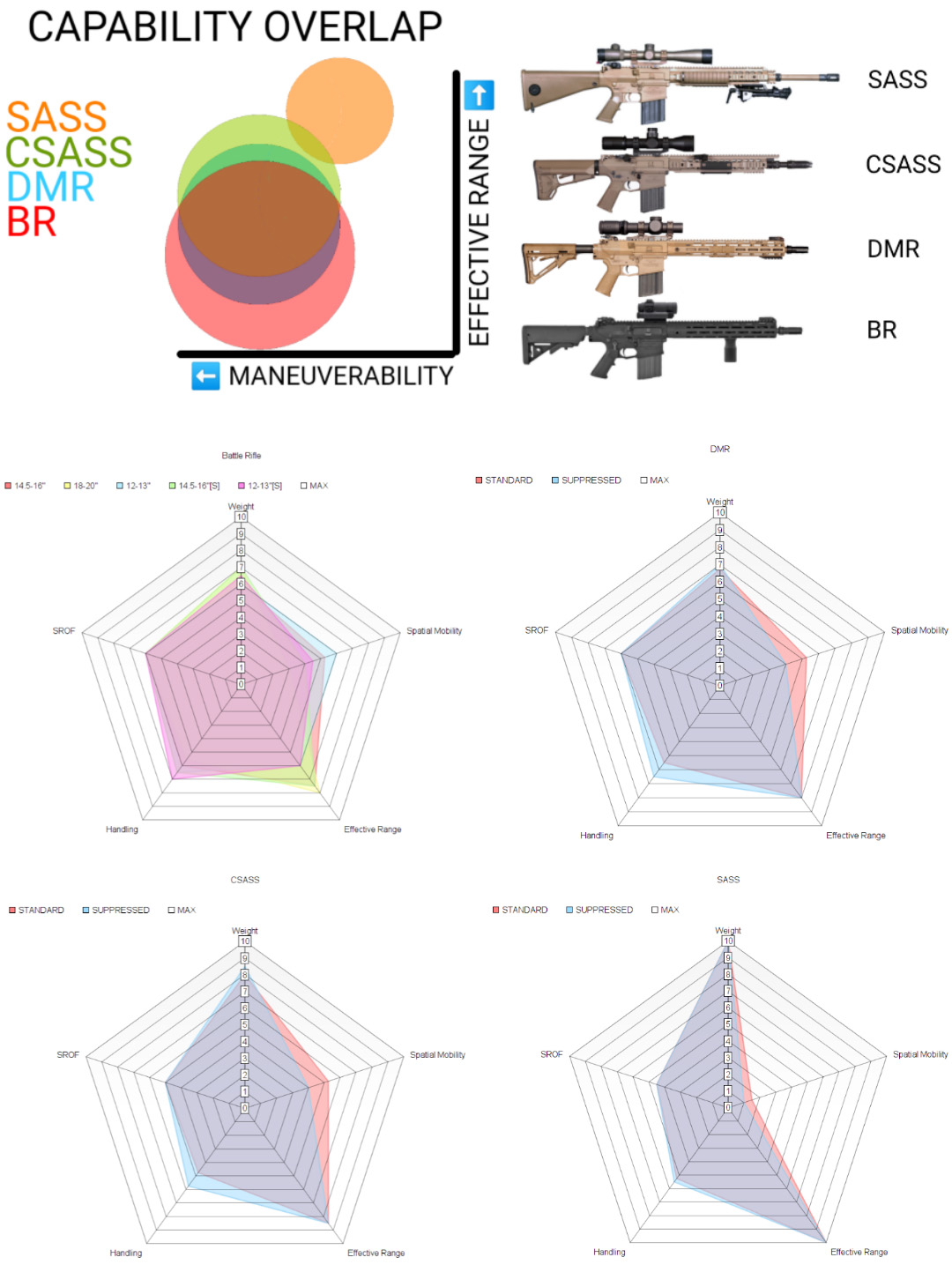

- BR: Lightest weight, widest maneuverability range, harder hitting and farther reaching than a GPR.

- DMR: Mid-range maneuverability and weight, capitalizes on ballistic capability with LPVO

- CSASS: Mid-range maneuverability and weight, capitalizes on ballistic capability with HPVO for sniper tasking

- SASS: Heaviest, least maneuverable, highest effective range, for Sniper tasking.

BR: Battle Rifle

Battle rifles were, once upon a time, the standard in small arms primary weapons. They were used by militaries across the world, and they came in different forms, most popular among them the AR-10, the FN FAL, the HKG3, and the M14 (and M1 Garand before it).

There were caliber variants of each, but they all came standard in 7.62×51 NATO, otherwise known as .308 Winchester (I know, the pressure specs are different, you knew what I meant.)

Eventually, they were replaced by Assault Rifles, and that’s how we ended up with myriad rifles chambered in 5.56×45, 7.62×39, etc.

The difference between a battle rifle and an assault rifle is the caliber or cartridge they’re chambered in. Battle rifles use what’s known as full power ammo, in the .30 cal neighborhood, and Assault Rifles use what’s referred to as intermediate caliber ammo, which is basically somewhere between pistol and full power rifle calibers.

Back in their heyday, battle rifles were the standard-issue infantry weapon, and the majority used iron sights. The same was true for assault rifles, which had replaced battle rifles as the main primary small arm by the point optics as we know them today started to become more popular and widely used.

Although some lesser developed countries continued to use battle rifles (and some do even to this day,) they didn’t really return to prominence until the GWOT kicked up and the long distances of Afghanistan sparked a desire for something that had a greater ballistic and terminal effect at distance, 5.56 ammo having not yet come along in its development to where it is now.

M855 left a lot to be desired, in terms of performance. With a newfound appreciation for 7.62×51 delivered from a semiautomatic weapon, older existing designs like the SR-25, M14, G3, and FAL saw increased development to improve their capabilities across the spectrum, from battle rifle applications all the way up to precision usage.

At the same time, however, new weapons like the HK417 were developed that were built around optimizing the delivery of 7.62×51 ammo and capitalized on improving the design features of the weapon altogether.

Today, battle rifles come in all shapes and sizes, but mainly in carbine form compared to the older and longer varieties. They are typically paired with the same optics as their 5.56 counterparts to keep the added weight of the weapon down.

Shorter barrels and smaller optics for BRs are helpful once you start adding suppressors and lights and things like that. They carry lesser ammo typically (with 20-25 round mags being the norm), but the point is to increase the lethality within the same space/area the squad would be expected to work.

That’s not to hint or suggest some stupid notion of stopping power, where bigger bullets mean bigger damage. But they do mean bigger holes, better wind resistance, and increased effective range. They also tend to fare better against barriers, though that’s a double-edged sword when it comes to penetration and being aware of your arc of fire.

If we’re being honest, in the same use envelope as a GPR, there’s not much more a BR will be able to provide for you besides a flatter trajectory over the same distance, and that better barrier penetration, but at the cost of lesser and heavier ammo and in some cases a heavier gun.

So why would someone rock a battle rifle? Besides the stubborn nostalgia that comes with the desire to emulate the warriors of old, basically, it’s because you have a lot of 7.62×51 on hand, and/or you wanna motherfunk the bad guys and give them more reason to stay dead.

I’m just kidding, there’s more to it than that.

One additional benefit the Battle Rifle holds over its smaller General Purpose Rifle cousin, again related to its ammo, is the effective range by default. Before anyone flips out talking about how 70+ gr 5.56 ammo is just as capable just as far as 7.62×51, stop and take a minute to think about this. Out to 600+m, the fancy 5.56 is at the tail end of its performance envelope, and the 7.62×51 is still thriving in its element.

But that’s beside the point.

Pretend you don’t have any of the fancy ammo. You’re slinging ball. XM193, M855, or M80. Why? How could you let this happen to yourself? Why wouldn’t you have better ammo?

Maybe you did. Maybe you used it all up. Or maybe the aforementioned varieties were the easiest to buy cheap and stack deep. This isn’t an unfamiliar situation now. As a matter of fact, this is what most people do. They buy blaster ammo in bulk and then get the premium stuff on top of that to save for a rainy day. Well if it’s hurricane season and you’ve got rainy day after rainy day, now you’ve got some ballistic performance factors to take into consideration.

Without splitting hairs, if ball ammo is the order of the day because it’s the easiest stuff to find in quantity, now the Battle Rifle takes the effective range hill. There, it reliably delivers terminal performance out to a further distance, and bucks the wind better on the way out there.

The ill-fated ICSR (Interim Combat Service Rifle) was an initiative to restore the Battle Rifle to primary small weapon status. This was based on the notion that the new M80A1 variant of 7.62×51 would fare positively against body armor plates used by near-peer threats.

Although this move back to the Battle Rifle from the Assault Rifle as the main primary infantry weapon was killed in its crib by those that felt carrying less (albeit heavier) ammo with increased recoil wasn’t the right move, it speaks to the efficacy and added capability benefit 7.62×51 carries with it. With the right variety of ammo, Battle Rifles are certainly effective, despite their antiquated characteristics.

They get more interesting when you further optimize them to take advantage of the ballistic and terminal capabilities of 7.62×51. Therefore, assume going forward that the Battle Rifle category is the only configuration that doesn’t always inherently have free-floated rails for improved accuracy, and all following categories do.

DMR: Designated Marksman Rifle

We’ve got ground to cover here. Which, incidentally enough, is the point of the DMR, not unlike the SPR. I’ll start with the technical details and expand on the role of the Designated Marksman, then get into the nuance of the murky waters we’ve set out to navigate in this article.

In the world of AR-308s as they exist today, the DMR is a battle rifle with a barrel not shorter than 14.5″ or longer than 16″ and equipped with an LPVO with a minimum magnification range of 1-6x, though it can go up to 1-10x in the same footprint/size of optic. The point is basically to do the same job as the SPR in the hands of the squad’s Designated Marksman, with a large frame AR-308 weapon.

We have seen this in military hands at least three times in the last two decades: Most recently, the M110A1 HK417 paired with the Sig TANGO6 1-6x LPVO in the SDMR configuration. Before that, the M110K1, 2, and 3 paired with the likes of the Leupold CQBSS 1.1-8x LPVO. Before THAT, in the early GWOT was the aforementioned Army version of the Recce Rifle, an SR-25K carbine with a Schmidt & Bender 1.1-4x LPVO (the state of the art at the time).

With the LPVO on a carbine length AR-308, you have equipped the weapon with a tool to take advantage of the extended-range capability of the 7.62×51 or 6.5CM round, but continue to allow you to 1x stuff like indoor or close-range work if needed.

The reason for this is based on doctrine, or in layman’s terms, why you would want that capability from your rifle.

“An SDM does not work from 300-600m. He works from 0-600m, since he is part of the squad. That is why the rifle is fielded with a 1-6x optic.” – Ash Hess, re: M110A1 SDMR.

If we’re being honest, MOST AR-308 carbines that are out there in private hands these days are configured in DMR form with the presence of an LPVO, because it makes sense to have glass on the rifle to take as much advantage as possible of what the rifle and the round it fires is capable of.

You, therefore, wouldn’t be wrong to notice or point out that there’s a large degree of overlap between the BR and DMR, which brings us back to the question of the Recce Rifle: If everyone has a “Recce Rifle” in the form of the GPR, do they all have Recce Rifles, or is this the new general-purpose configuration? Or in this case, is everyone with a DMR configuration a Designated Marksman?

The answer is Yes and No.

Yes, while everyone ought to be capable of Designated Marksman performance as a shooter (in a perfect world), No it wouldn’t make everyone a Designated Marksman.

There’s an argument to be made, in observation of the degree of overlap between the BR and DMR, for calling it a “Dual Role Carbine,” which isn’t inaccurate but it’s also vague, and a lot of things could be called that depending on how the dual roles are defined, which can end up being a mess. “Heavy General Purpose Rifle” or “Heavy Carbine” has also been suggested, but I was never a fan of assigning a descriptor of weight to refer to size; they all get heavy once you start attaching things to them. My HK416 is a heavy carbine. See where that ends up going?

So what stops the DMR configuration from being the GPR of AR-308s? Because we have to account for the task that the configuration is optimized for. In particular, barrel length plays a role here, and that’s why we had to delineate categories.

Q: “Why is the barrel no shorter than 14.5″ or longer than 16″ for a DMR?”

A: I can’t speak to 6.5 CM personally other than to say while typically being fired from long barrels, the shortest I’ve ever heard of it being done while still retaining its precision capability is 14.5″. But if we’re talking 7.62×51, 16″ and up is where 7.62×51 typically likes to hang out in terms of barrel length if you’re still trying to get long-range effectiveness out of it.

A 14.5″ barrel (14″ in the case of the SCAR MK17) is basically pushing the limit of how short your barrel can be while still getting an appreciable performance at distance (roughly 600-700m, depending on twist rate). Shorter than that, well, now you’re no longer optimized for DMR tasking.

So, while there are 12.5″ and 13.5″ barreled varieties of AR-308s out there (like the HK417A2 and LMT MARS-H, respectively), and they very well can and do have LPVOs attached to them, the 14.5-16″ barreled configurations will do the job better, as data and history will show. The M110A1 and any M110K series rifle demonstrate this clearly when fitted with an LPVO.

Q: “What about a longer barrel like 18″ or longer?”

A: The weight and maneuverability trade-off isn’t really worth it for what you’d expect to be doing with the DMR configuration as described, honestly. Those barrel lengths are best suited for a configuration more appropriately equipped to take advantage of the ballistic performance those barrels provide. We’ll cover that later.

What’s in a name?

SPR vs DMR versus “Scoped Rifle”

I know this is one you guys have been waiting for me to explain, so let’s get to it. Why do I only use DMR and SPR to refer to the configurations described in the respective slides, when “DMR” has doctrinally been used to describe “The scoped rifle the designated marksman is holding”? Because that’s vague, but there is such a thing as oversimplifying. Both of those are confusing, and we’re here to clarify the matter.

I am among those that use “SPR” to describe “An accurized AR chambered in 5.56 and optimized for precision shooting at long range,” and only that, because… that’s all “SPR” has ever been used to refer to in the AR world.

That’s exactly what the Mk. 12 SPR — which inspires so many AR builds — really is.

There is no doubt or confusion as to what kind of rifle configuration or intended purpose thereof that you’re referring to. Doesn’t matter who used it or what type of unit they used it in in the military. Everyone understands this. That was the easy part.

DMR, on the other hand, has been used to refer to both 5.56 and 7.62×51 rifles used in the Squad Designated Marksman role described. Hell, the M16-based SDMR is testimony to its likeness towards the SPR. That’s why it’s in that category, and why the category was named after it (since it was describing only 5.56 ARs).

But remember, this is for regular guys. Not cloners, not dogmatic doctrine followers, or people that really nerd out and get into the weeds otherwise.

So since DMR has been used to describe weapons of both calibers, where else do regular guys usually and most likely encounter the phrase “DMR” outside of the firearms industry?

Video games.

LOL. Preposterous, right?

But seriously, think about it. For many, video games are a gateway into the 2A community and the initial perusal of what all the firearms industry has to offer. It piques the interest of the player as they cross the threshold into the 2A world, and at first seek the guns they’re most familiar with: the ones they see in the games they play.

Now think of all the first-person shooter games out there and the most popular among them. Have you ever seen any of them use “DMR” to refer to an intermediate caliber weapon? No, you haven’t. The most recent examples that come to mind are from Halo, Call Of Duty, and Battlefield.

In Halo Reach, Halo 4, and Halo 5, you have a rifle that is straight-up referred to as DMR, and it is not an accurized version of that game’s assault rifle optimized for precision use. It is larger, with heavier recoil, and likewise heavier hitting rounds, paired with a magnified optic.

In the 2019 Call of Duty: Modern Warfare you have a category of weapons called “Marksman Rifle” that contains the likes of the M14. They call it the EBR-14. This is a callback to several points over time the M14 has been used as a DMR in military hands.

More recently, in Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War, the M14 returns in the Tactical Rifle category. But do you know what it’s called in the game? “DMR 14.” How’s that for on the nose?

Finally, in Battlefield 4, there is a whole category of weapons called “DMR” that contains the likes of the SR-25, M14, and SCAR-H, all of which have been used in that capacity in real life.

I know the SKS (an intermediate caliber weapon and therefore not even a battle rifle), and other weird stuff can be found in both the Modern Warfare 2019 and Battlefield 4’s DMR categories, but we can chalk that up to the game developers being misinformed and/or using it as a catch-all category for “guns that hit harder and farther than the assault weapons but aren’t sniper rifles” in general, or both.

We see that happen regularly, where for the sake of balancing weapons, two weapons in two different weapon categories that fire the same bullet in real life will do two different amounts of damage between them. This makes no sense but isn’t relevant to our purposes here.

To the point: in either case, you have multiple instances of 7.62×51 rifles (or the sci-fi adjacent counterparts) being referred to and associated with the terminology DMR or Designated Marksman Rifle. In that particular use/role, in a form of media that is widely consumed by regular guys and potential newcomers to the firearms community.

It also helps that, following this gateway into real firearms, industrial use of the phrase DMR by myriad manufacturers is more commonly seen when referring to large frame 7.62×51 rifles with an implied precision capability.

Having said this, the configuration parameters of the DMR category here are informed by two of the most renowned and highly regarded examples among the initiated in our circles: the KAC SR-25 M110K1, and the HK417 M110A1 in its SDMR configuration.

So while DMR has over time been used to describe both 5.56 & 7.62×51 AR platform rifles on the military side of the house, it is more commonly colloquially associated with rifles chambered in the larger caliber among the gun-owning public. SPR, however, has only ever referred to a 5.56 AR.

Q: “But the term DMR has comprised everything from a bone-stock 14.5” M4 Carbine with an ACOG to 22” M14 variants in Sage EBR chassis systems, right?”

A: You can start to see how doing things the doctrine way can get confusing, but I’ll bite. Let’s try it that way.

Hand me that DMR over there?

Which one?

Not the General Purpose Rifle, the DMR.

No, not that one, who the hell intentionally picks up an M14 when an AR platform is on the table?

Well, which DMR do you want?

Look at all this extra communication and narrowing down bullshit we have to do because you want to be pedantic.

“They’re all just scoped rifles, so let’s just call them scoped rifles.”

Yeah? Hand me that “scoped rifle” over there from that pile of differently configured scoped rifles.

And there we go again.

See how you can complicate things one way and oversimplify the other way?

Therefore, I need to say three letters, you need to know exactly which rifle and optic combination I’m referring to just by looking at it. If I say SPR, I want the 5.56 AR that’s obviously geared towards precision use and is also cross-compatible with the squad’s GPRs. If I say DMR, I want the 7.62 AR carbine with the LPVO on top.

They both do the same job but are delineated by caliber because you can visually and tangibly tell the difference between them, and you already know DMR means “the one with the bigger magazine” based on what’s commonly associated with the phrase anyway.

See how simple that is? Classification by analyzing configuration weighed against intended use, with an easily identified caliber-based delineator criteria to tell apart two different rifles with similar jobs/capabilities. And all you have to say is three letters. Until there are more letters.

SASS: Semi-Automatic Sniper System

Were I progressing from small to large, CSASS would’ve been next on the list, but to really get a good grasp on what that is and how/why it came about, we have to cover SASS first since it’s the progenitor to CSASS.

So the most important word to take note of in the SASS acronym is the third, “Sniper.” That’s who the SASS was primarily developed for. The Army wanted something semi-automatic to be deployed within the same use envelope as the older bolt action M24 (Remington 700) rifles the snipers had been using up to that point.

The M110, originally XM110, a further developed version of the Mk. 11 Mod. 0 configuration of the KAC SR-25, is what was officially selected to become the M110 SASS. This rifle set the tone or the standard for every other comparably configured rifle the industry would produce; they even kept “SASS” in the name to associate their comparable to alternative with the real deal, as you can see in the slide.

There are minor differences, yet more similarities among the configurations, which optimizes them for the Sniper task and intended role/use thereof: longer barrels, free-floated rails, high-powered glass, and larger calibers. Thus, the configuration category intended for such use was so named: SASS.

It’s important to point out that the SASS configuration is a dedicated Sniper rifle setup because it’s NOT a “squad” weapon. Another way to look at is like this: The fire team or squad we spoke of previously is considered a company/platoon level element. They are the majority of the fighting force; more of them are around because more of them are required.

So where your GPRs and SPRs are squad level in terms of commonality (where BRs & DMRs are the larger caliber alternative, and CQRs and PDWs are meant for specialized tasking at the same level), snipers are a battalion-level element (usually up to three 2-man teams).

In layman’s terms, there are fewer of them to go around, as they are a yet further specialized task, beyond that of the Squad Designated Marksman. Therefore, their rifle needs to be optimized for the capability that the Sniper role calls for. This comes with some trade-offs, as any of these configurations do.

With a longer, heavier rifle further weighed down by high power optics, and sometimes CNVDs, along with lights, lasers, and suppressors, the configuration isn’t meant to be carried around moving door to door and room to room. It could be used that way, like we saw done with an M110 by Bradley Cooper acting as Chris Kyle in the movie American Sniper, but it’s hardly optimized for that type of work and therefore wouldn’t be the first choice for it.

This is why we later see a CQR (a Mk. 18 Mod. 0 CQBR, to be precise) utilized for Direct Action purposes (being far more optimized for such use), while the M110 is set up in a hide being used to collect intel and provide overwatch.

Though it looks like a giant M4 or a Battle Rifle with a big scope on it (by virtue of it being an AR platform rifle), it’s stressed that you do not treat it as such, but rather as a bolt action-like precision capable rifle with a faster firing rate to more quickly address multiple or moving targets. This (the M110) is the rifle the Army asked for, this is the rifle KAC delivered, this is the rifle every other manufacturer with a likewise product compares itself to. You could fire off controlled pairs with a SASS, but if you do, you’re not using it for what it’s optimized for. It’s not for that.

So now that we know the SASS isn’t a squad/stack rifle, but it is very much a dedicated configuration optimized for long-range precision shooting such that a Sniper Rifle would call for, what role is it for? What are the guys that use it actually doing with it? In other words, for what purpose(s) would YOU, the discerning regular guy in the commercial market, buy, assemble, or grab a SASS configuration for?

You’re probably picturing the stuff you’ve seen in movies and video games that have come out in the last twenty years: ghillie suits, sniper’s hides, stalking, and sharpshooting from far away. But wait, there’s more! Let’s look at what the Army and Marines task their snipers with:

“The term Scout Sniper is only used officially by the Marine Corps, but it does not imply a differing mission from the U.S. Army Sniper. An Army Sniper’s primary mission is to support combat operations by delivering precise long-range fire on selected targets. By this, the sniper creates casualties among enemy troops, slows enemy movement, frightens enemy soldiers, lowers morale, and adds confusion to their operations. The sniper’s secondary mission is collecting and reporting battlefield information.” Section 1.1 FM 23-10 Sniper Training.

The Marine Corps is unique in its consolidation of reconnaissance and sniper duties for a single Marine. Most other conventional armed forces, including the U.S. Army, separate the reconnaissance soldier or scout from the sniper. In the U.S. Army, the 19D MOS, “Cavalry Scout” is the primary special reconnaissance and surveillance soldier and the term “Infantry Scout” refers to specially trained infantrymen that function in a reconnaissance and surveillance capacity. The term “Sniper” refers to a specially selected and trained soldier that primarily functions as a sniper. Most military forces believe that the separation of reconnaissance and sniper capabilities allows for a higher degree of specialization.

So now we’ve got three additional uses we’ve already covered before: Long-range precision (obviously), intel gathering (recon), and overwatch (at distance). Remember how we talked about the effective range capability of 7.62×51 back when we were talking about Battle Rifles? That long accurized barrel with free-floated rail really helps push the bullet well out to its maximum effective range, for those moments when you’ve gotta reach out and touch someone, well out to 1000m and beyond when you’re using the right ammo.

That HPVO is good for collecting information from a distance, including PID and target discrimination, because of the higher magnification and therefore observation capability it provides. Let’s talk more about HPVOs for a minute.

HPVO: High Power Variable Optic

Back during the advent of the M110, scopes that topped out at 10x magnification and started around 3x were considered HPVOs and suitable enough for the job. Today that’s no longer the case. Optics technology has progressed to a point where within the same size optic or smaller, you can have a scope that offers up to twice the amount of magnification. You can have more if you’re willing to sacrifice your low-end magnification, though we don’t usually see the 5-25x or 7-35x stuff on SASS or CSASS rifles that often.

Case in point: the HPVO is defined as a magnified optic with a MINIMUM max magnification of 10x (to account for the older stuff,) but in accordance with modern technology that’s available to purchase RIGHT NOW, you’re looking at a top-end magnification of 15, 18, or 20x. Because why wouldn’t you get that for an actual working rifle SASS configuration?

I was asked, “You define the difference between a SASS/CSASS and a DMR as based on the use of a ‘SASS-class high power variable optic,’ however, the ‘stock’ optic for the actual SASS (M110) was a Leupold MK4 3.5-10x. How then does one classify an SR25 APC with a Vortex Razor Gen. III 1-10x? Is it a CSASS by virtue of the fact that it has a 10x top-end IAW the SASS? Or is it a DMR because it has a 1x bottom end? Or is it a BR because it could be used as a ‘heavy general-purpose rifle’ covering the LPVO range?”

A 16″ barreled AR-308 with an LPVO in the 1-6/8/10x range? That’s a DMR configuration. So yeah, back in the day the M110 SASS had an optic with a 10x top-end magnification. Today…who cares what was all the rage in 2007? Why would I put a 1-10x LPVO on a SASS or CSASS instead of a 3-18x or 4-20x, which is that much more optimized for what either configuration would be used for?

We’re talking about what’s available today, right now, not what’s clone correct. The M110 is rocking a 3.6-18x Leupold Mark 5HD nowadays anyway, which goes to show even the Army has a higher appreciation for capability over what’s traditionally specified or “clone correct.” Moving right along.

Stock configuration is optional, though, in all honesty, where most SASS configurations started with or still utilize a modern form of fixed stock, it’s becoming more common to see them equipped with adjustable stocks. Even the M110 has upgraded to a B5 stock on a LAW Tactical folding stock adapter hinge, so this one’s up to you really.

Remember how I said, “If you put a suppressor on a rifle length configuration, well… Close Quarters probably isn’t your first job.”?

With a SASS, suppressor or not, you probably aren’t even expecting to be doing as much walking beyond moving between hides and overwatch positions. Remember: the rifle configuration is optimized for the tasks of long-distance intel gathering, target discrimination, and precision shooting.

It’s long and it’s heavy, so you’re giving up maneuverability in exchange for something that’s really good at that long-range requirement. That said, it is not at all uncommon to see a SASS equipped with a suppressor for stealth and signature reduction purposes.

And, you know, more casually, you see a lot of SASS-esque setups in the ELR/PRS sections of the competitive crowd. Some guys like being able to hit targets really far away, and what would you know, the gas guns they do it with are quite SASS adjacent in their configurations, if not exact.

Where I work, we call that a clue.

On the other hand, the CSASS is a little more forgiving in terms of maneuverability, sliding away from long-range precision on the scale just a pinch.

Let us continue.

CSASS: Compact Semi-Automatic Sniper System

There is not really a whole lot to say here. Having covered everything about what makes a SASS and why, the difference between it and the CSASS is denoted by that added letter: C, for Compact.

Same exact job as a SASS, but shorter on both ends.

But how short? Honestly, it’s just a DMR sized rifle, with a SASS-class HPVO optic on top. Other than that there’s no difference. Same caliber, same barrel length, same collapsible stock.

We get the configuration category name and parameters by looking at the two most prevalent examples of a CSASS rifle, the M110A1 & M110K1, so named (or developed for such intended use). In accordance with that intent, when the military opened the doors to the industry to build them the CSASS they were looking for (for which a variant of the HK417 was selected as the M110A1,) several of them developed 7.62×51 carbines that were commercially referred to or associated with the name CSASS. This further cemented the parameters of the configuration among casual spectators and hobbyists.

But until the M110A1 took the contract, the M110K1 (another version of the KAC SR-25, and a carbine version of the M110 SASS at that) set the tone and was what everyone thought of as the shoo-in for the job, when the RFI for the CSASS first came about.

This is especially since variants thereof were already being used by SOF, well before the M110A1 came along and took the title officially.

The interesting thing here, in the case of the M110A1 and M110K1 before it, is that they’ve BOTH been used in CSASS and DMR configurations. We can look and see the difference between them depending on who’s using the rifle for what purpose in which configuration.

In both cases, it’s the SAME rifle, with a different optic: 1-6/8/10x LPVO on the DMR, HPVO on the CSASS. It’s literally the only way to tell them apart.

“Herr-durr, the M110K1 + Leupold Mark 8 CQBSS 1.1-8x LPVO was never doctrinally denoted as a DMR.”

Yeah, but when you compare that to the M110A1 SDMR configuration and the intended use thereof, along with the other examples on the DMR slide… it’s the same thing in terms of mechanical capability, so let’s just go with it.

As a matter of fact, the CSASS configuration of the M110A1 existed first, before the DMR version. When the Army wanted a new DMR, did they just hand the SDMs an M110A1 CSASS and say “Here ya go buddy, get to steppin’”? No, they reconfigured the rifle with a different optic (1-6x LPVO) cause that’s what was optimized for the DMR’s intended use. Nothing else changed.

The optic (likely accompanied by an offset or 1200 mounted MRDS) is the only difference. It doesn’t matter if a Squad Designated Marksman never carried an M110K1 in the infantry, the configuration lent itself to the same purpose and manner of use because that’s what it’s optimized for.

So… if SASS is a thing, why would somebody want a CSASS? What’s the difference there?

Well, notionally at least, the mission/tasking is still the same, but the trade-off of some long-range precision capability in exchange for mobility and maneuverability is (again, notionally) for the following reasons.

Compared to a SASS, a CSASS configuration is, has, or enables:

- Lighter weight and smaller size for more mobility & maneuverability in urban areas.

- Increased Spotter lethality (especially where the Sniper is using a larger caliber/”big bore” bolt action rifle).

- Less conspicuous, and therefore more closely appears to be an M4 at a cursory glance, making the sniper harder to differentiate or tell apart and therefore target, from the OPFOR perspective.

- Same task & capability requirement, but in a smaller AO (like an urban environment), therefore not requiring as much long-range precision capability.

So you’re doing the same job as you would with a SASS in terms of intel gathering, observation, and overwatch, and you still have a requirement for precision sharpshooting at range. You’re still doing it from hides/concealed positions and vantage points or stalking between them. You’re just doing it in a smaller area where your targets aren’t as far away as they would be if they necessitated the capability of a SASS at farther distances.

Same precision capability as a DMR between the barrel, free float rail, and ammo, but the change in optic to the same variety you’d see on a SASS optimizes the configuration to be used for the same tasking as a SASS, albeit from not as far away.

That’s really all there is to it for the CSASS: its DMR with more optic, and a different job. It’s that simple.

That concludes the main eight configuration classification categories of rifle types. Some of you may be wondering about other configurations that don’t quite fit into any of these eight as described. They are accounted for in the ninth and final category, the one for all the weird stuff you might see out there, or the stuff that just isn’t as common anymore these days in terms of standards.

Hang tight, for jimmies shall rustle.

XPR: Exceptional Purpose Rifle

So, this isn’t really a configuration category as much as an “Other” category.

This is the place for whatever doesn’t fit into the other categories, either because it mixes and matches parts without necessarily bringing all the complementary capabilities along with it, or it’s some oddball “Why would you even do that?” sort of thing. It could just also be uncommon because it’s obsolete and fallen out of relevance or considerable preference compared to newer tech that offers the same or greater capability in a smaller package.

Dedicated hunting rifle? Small frame gun with a weird boutique caliber that starts with a 6? HPVO on a carbine or SBR AR-15 that won’t increase the effective range anyway? RDS on an SPR? Barrel length that’s suboptimal for the caliber choice? A configuration that fell out of relevance and is no longer the standard?

You’re in XPR territory. It’s not a bad thing, it just doesn’t fit anywhere else.

“But the M16 isn’t uncommon!”

I know some of you are looking at the M16A4 and C7A2 in that slide and wondering how I could have the audacity to “other” such noteworthy war fighting weapons. The thing you have to remember is, this isn’t about classifying what the military uses. This is about classifying what the regular guy uses based on what the industry has to offer, which is further based on what the military uses. We do this by weighing the configuration against the intended purpose.

Mind you, that’s where we got the title of the article from; many an AR in private hands was put together the way it was because it was “inspired” by something the .mil uses.

“But the National Guard and Marines…”

Give it a rest, guys. Between the M4 & M27, the M16 (which in the past would have been considered a General Purpose Rifle here) is on the outs. They’re still out there in armories, sure, but even the .mil has been trending away from these.

So we’re looking at what’s commonly used in circulation amongst the regular guy crowd based on modern tech trends.

And listen, I’m being honest…I asked, and there’s no one I could find that would prefer to choose something like an M16A4 clone or an earlier/retro version of the M16 configuration, or a C7A2-ish joint. The capabilities of newer shorter configurations like those addressed here, along with the capability of the accurized SPR builds, outweigh the idea of a long musket that hasn’t been accurized.

There’s no one out there who has such a configured rifle as their number one go-to gun if they have a choice. There are plenty out there as retro-themed collector pieces, but in a world full of GPRs, SPRs, and CQRs as they exist currently, M16-like configurations aren’t nearly a first-string pick these days by any considerable margin among those with options

Wildcat Pioneers, this is all you.

You guys find these weird nonstandard cartridge options and figure out how to put them in an AR and… that’s about as far as it goes. 6.5 Grendel, 6.8 SPC, 6ARC, .224 Valkyrie, .300 Whisper? .458 SOCOM? .264/.270/.277/.280?

I’m sure you all have your redeemable qualities, however, you’re all weird in that “before it was cool” hipster-y kinda way. The thing either hasn’t hit its mainstream stride yet (or won’t ever). That’s not a knock, it’s just uncommon or unusual.

Hunting ARs are an obvious candidate here, they’re a fighting rifle platform that’s been watered down for dedicated hunting use. The only reason they’re considered here is that they’re ARs, optimized for a non-fighting use.

There used to be weird ban-era stuff out there like the Bushmaster XM15 carbine that you just… do not see anyone elect to put together anymore. In ban states, you see stuff similar to it, but it’s not a choice as much as it’s a legal requirement or workaround.

The term Exceptional describes some of the funky stuff I’ve seen out there— like an M4A1 Block II with an HPVO, which is like… a CSASS version of an SPR (CSPR?). But it’s an oddity, all the same, considering that the effective range and ballistic performance of the 5.56 round out of a 14.5″ barrel aren’t very much complemented or further enabled by the high power glass.

I’ve seen it done, but not often. It always struck me as an on-site combination of components to fill a gap in a pinch based on what was available on hand rather than a purpose-built solution. Kinda like 16″ barreled SPR builds with high power glass or the old Recce Rifle stuff from the early GWOT.

But again I digress.

Examples of an XPR aren’t limited to the pictured examples, that’s just all I could fit on the slide. But you have an idea of the logic being applied here. ARs can be made to do a lot of things; they don’t all typically have a place. Sometimes it’s just because/why not, sometimes it’s obsolete, sometimes it doesn’t make sense.

That’s the nuts and bolts of the XPR category of rifle types: no barrel length, optic, or cartridge parameters, not really particularly optimized for any task the configuration varieties already address, because we have eight other categories for that, and if it doesn’t fit in one of those…

You’ve got yourself an XPR: a rifle of exceptional purpose or unusual configuration. Because it’s an exception to the eight (8) previous configuration classifications.

I’ve said it already, but I want to leave you with this: a lot of these configurations can be used to do another configuration’s job. Overlap is to be expected, especially in capability, but the question to ask, and ultimately the answer that separates them, is “Is the configuration optimized for the intended role?”

Can a GPR do an SPR’s job? Yeah, sure. But an SPR will do it better. Can a BR do a DMR’s job? Yeah, but not as good as a purpose-built DMR configuration. Can a CQR be used as a PDW? Sure, but it wouldn’t be as readily concealable and deployable as a PDW, and there’s also ballistic performance to take into consideration.

Those are just a few examples.

A scoped rifle can be a scoped rifle at the end of the day. But its configuration gives us a clue as to what role it’s optimized for, and thus how to best utilize and therefore categorize it.

Now for the most important thing: these things move.

They evolve with time, they aren’t set in stone. As technology gets more capable, and smaller, and lighter, categories will overlap so much they will absorb into each other and become the same, and therefore fewer in number. The more capabilities a rifle can reliably provide in a standard generalized form, the less need for specialized configurations there will be. And that’s to be expected.

We’ve seen it happen over time, and we see it in these category slides. Until we’re shooting laser/beam/plasma rifles with digitized optics capable of ridiculous levels of magnification based on image rendering technology, there will never be one bullet delivered from one rifle configuration with one optic that can do every job. So there will always be different configurations out there — but the names might not always make sense. So the approach I’ve always used to navigate them that’s worked best is to look at how the rifle types are configured weighed against their intended purpose, and associate that combination with the name most commonly associated with that form factor.

From that, this system.

In the current era:

The GPR should summon in your mind something akin to an M4A1 or M27.

The CQR should make you picture something like a Mk. 18.

If I say I want to do an SPR build, you should know that I’m talking about something like or inspired by the Mk.12.

PDW should tell you, a weapon smaller and more concealable than a Mk. 18 with a caliber optimized for that size.

Battle Rifle? A lighter weight 7.62×51 fighting rifle that packs a punch out to a greater distance, and capitalizes on speed and maneuverability.

DMR? A Battle Rifle configured to take advantage of its ballistic capability at distance.

SASS should tell you “A long heavy large frame AR conducive to Sniper tasking.”

CSASS? DMR with big glass, also for a sniper tasking.

Finally, XPR should tell you, something that doesn’t fit into those previous categories.

In the future, who knows? Some of these categories might go away like the way GPR absorbed and usurped “Recce Rifle” as a unique configuration. We may see new categories based on new technologies and requirements. Either way, it will be interesting to watch how things develop.

Hopefully, this will be of some use to you. Ideally, it makes the sea of products the industry has to offer that’s inconsistently named after military small arms easier to navigate and the different combinations of products easier to understand.

What you have now, I hope, is an easy-to-remember and easy to disseminate system of shorthand. Take it and pass it along. Next time you have a friend wondering how they should set up their AR, show this to them, and give them something to think about. Maybe it will help them get the most out of their first or next rifle.

Clarifications

Reviewers

I’ve been an actively involved member of the 2A community for almost 15 years at this point, and more recently the “industry” itself. In that time I’ve learned a lot by observing and seeking out the highest quality information sources and met a lot of extraordinary people in the industry. I’ve been privileged to make many friends among them, and with many civilian and professional end-users as well.

While writing this I ran all of it, piece by piece, by some of the most experienced and knowledgeable among those friends. I wanted to make sure I wasn’t overlooking anything, or leaving anything out, or saying anything factually incorrect. I wanted to make sure it made sense, and that my logic was clear and easy to grasp. It was wholly approved by everyone I asked to analyze and critique it.

They know who they are, and I’d like to thank them for their assistance.

Those who disagree with the idea

These people will think it absurd, that one would form categories based on configurations and the uses and names thereof that borrow from .mil naming conventions without strictly following the doctrine or the reasons those configurations were developed and named so. That’s okay. One last time for good measure: this was not written for them and has zero bearing on the way the .mil does things.