This article was originally posted on Breach Bang Clear here.

The Elcan SpecterDR is an oft-maligned Low Power Variable Optic. It’s an LPVO that stirs up substantial contention, particularly in social media (and only slightly less so on assorted forums). Is that an engineered controversy and uncivil discourse because people just want to be outraged, or legit criticism? We weren’t sure, so we went to a compellative pantomath (one of several who writes for us, actually) and asked him why the Elcan is the optic of choice for one of his rifles. He jotted down just a couple of words right quick — with the admonition that we make it clear the appropriate optic should be chosen for an intended purpose. One size does not fit all, and any choice should be a reasoned one. Anyway, we reckoned we’d share. Mad Duo

Chin Up

A comparative analysis and end-user feedback:

Why I chose the Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x

A friend of mine said, “Elcan weapon sights, be it the M145 or SpecterDR, are garbage fires. You cannot change my mind.”

Challenge accepted. Well, I might not change his mind, but I can better inform yours when that’s the most some would say without substantiating that opinion any further.

While I can’t speak to the M145, having never used one, the focus of this article will be the SpecterDR, of which I have owned three over the years, currently one.

Intent: For months, Reeder [Breach-Bang-Clear’s chief editor, currently talking about himself in 3rd person as well as in italics] has been asking me to write an Elcan review. I had no problem doing it, but I waited a while for a couple of reasons. First I wanted to get a class out of the way where I’d be using it in a new configuration compared to the last time I wrote about it. Next, I wanted to write a review that isn’t merely a review that talks about why I like what I spent my money on, but informs the reader of what to truly expect of the product, and understand what lessons and developments went into my setup, both personally and institutionally.

Knowing that over the years the Elcan SpecterDR has been a victim of criticizing hearsay, I sought feedback from those who actually used them in the most adverse conditions overseas, to supplement my own findings.

SECTION 1: Task & Purpose

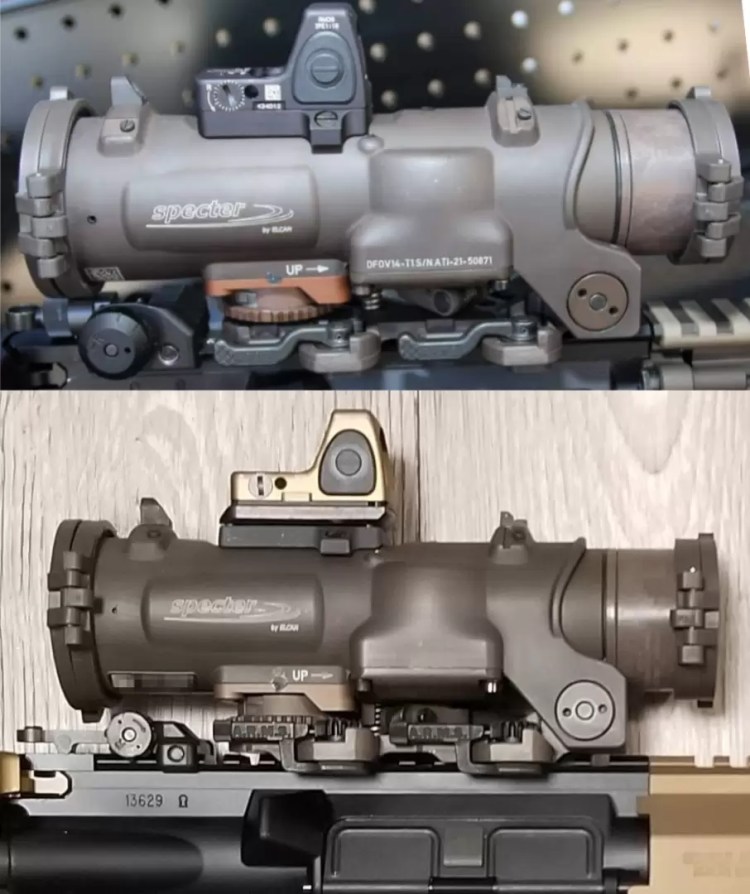

Before we get into that, let’s review what I have: Currently situated atop my HK416 upper that I wrote about previously is an FDE Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x, with the 5.56 calibrated reticle. I’ll go over what I selected it for and why again, but there have been some changes to the setup I’m going to focus on also.

Previously, the Elcan was there, but the Aimpoint P1 ACRO was mounted to the Valhalla Tactical Rukh, a fully adjustable offset mount with 90 degrees of adjustment range. It was mounted just forward of the Elcan, and set just so that it lined up with the parallel zeroed laser of my MAWL, or as near as I could get it.

The Rukh I have is the 1.93″ height variety, and it was there for two purposes: First, to provide a mounting solution for a 1x optic with unlimited eye relief, in this case, an MRDS (Micro Red Dot Sight) to avoid contending with the Elcan’s eye relief, which is narrow compared to most LPVOs, even at 1x. Next, to therefore also provide a means to aim passively through the optic while using Night Vision (without having to put the Elcan on a funky riser and trying to get my NV to cooperate with the eye relief on 1x). It was a successful setup and did as it was intended.

But, that was Plan B.

Now, the ACRO is mounted ON TOP of the Elcan SpecterDR, via the saddle mount made by REPTILIA Corp. This was what I had originally intended to go with in order to mount the ACRO to my HK416 upper back in 2019, but complications from COVID put a pinch on manufacturing, and I hadn’t received it until late last year, months after I’d written my previous article regarding the same rifle configuration.

Now that I have it AND have had the chance to use the whole optics package for its intended purpose in a training setting, we’ve got plenty to talk about: The Elcan, the ACRO mounted to it, the saddle it’s mounted with, the idea of an MRDS piggybacked on a magnified optic and where it came from compared to why it’s popular today, and comparable alternatives.

First, the Elcan itself, and the focus of this piece. As I said previously, the problem I was looking to solve for my rifle was PID capability, and the ability to more precisely take shots at range, without being too heavy or taking up a lot of space on the upper receiver’s top rail.

Ooooh…so mysterious!

Given its form factor, I view and describe the Elcan in the same category of optics as the Trijicon 4×32 ACOG that came before it: a combat optic. In short, it’s a magnified optic that has a self-contained mounting system. In terms of size/footprint, it sits squarely on the upper receiver or within the confines of its top rail, without the need for a cantilevered mount that pushes the optic past the forward limit of the upper receiver in order to obtain proper eye relief in relation to the rear objective.

This keeps the weapon balanced, with the weight squarely concentrated in its center, which acts toward keeping the rifle from getting front heavy. This is helpful with any AR-15, but especially so with the HK416 upper, which is already more front-heavy than a typical AR between its barrel profile and the gas piston assembly riding on top of it.

Being all one piece and therefore not needing to level the optic in a separate mount is convenient, and lends itself further to the optic’s resilience; the Elcan is a stout optic. Commonly described as having been “built like a tank,” the optic could definitely be used as a blunt force instrument between its construction and its weight, which is considerable, but not as bad as it’s made out to be. More on that later.

With this, I end up with an optic that balances my rifle, doesn’t take up too much space, provides enough magnification at 4x to appreciably obtain PID and a clear sight picture from close quarters distance out to at least 500m, provides an illuminated BDC reticle that’s NV compatible, and is extremely durable and robust. Given the fact that it’s sitting on a 10.4″ barreled rifle that’s configured for CQB to medium range engagements day or night, and be used with night vision as well, it does what I need it to do for the weapon I put it on.

The glass is some of the highest quality there is to be had in the industry, extremely clear, and the BDC reticle is etched into that glass. This means it will always be there even if there are no batteries in the optic, and the reticle can never be damaged and knocked loose inside the optic like some wire reticle optics have been known for.

It is the third Elcan SpectreDR I’ve owned, so it’s not new or unfamiliar to me. The first two were also the 1-4x variety, the first was black and calibrated for 7.62, the second was FDE and calibrated for 5.56, and they were both earlier/older Gen 3 models, having been purchased in 2012 & 2014 respectively.

This one is a newer Gen 3 model (Gen 3.1 perhaps? 3b maybe?) that has a new battery cap that’s flat and has a flathead screwdriver-like slot, a change from the older raised and textured battery cap. Previously it was retained with a piece of string lanyard and required you to hold the illumination dial in place while you removed and fastened the battery cap to avoid spinning the illumination dial along with it. I asked a friend to call a contact of his over at Raytheon and he reported back that this was done to streamline manufacturing.

One thing about the Elcan that I’m not a fan of is the killflash accessory. There’s two reasons for this: First, if you have the Elcan on 1x and tilt your head within the eyebox and view it off-center, you can see the thick honey comb-like structure of the killflash and it occludes your vision. Second, and most importantly, if you tighten the killflash too much (it threads into the front of the optic) you can rotate the whole prism out of focus since it attaches to the same part inside the optic.

Imagine how I almost panicked when, after installing the killflash, I switched the optic to 4x, looked through it at a distant stop sign, and everything was blurry! Like coke bottle glasses level blurry. Once I figured out how and why it happened, I unfucked the optic by rotating the prism back into focus bit by bit until the sight picture at 4x was as clear as it was before. And that was the last time I ever installed the killflash. The only time I can ever see using it again is if I knew I’d be going into a force on force shoothouse class with this rifle, and only to protect the glass. I might even put one of the closeable scope caps on it at that point, but beyond that, I won’t be using it again.

SECTION 2: “But the internet said…”

Now that I’ve covered why I bought the optic and what I get out of it personally as per my intended use, let’s talk about some of the hearsay going around the internet regarding the Elcan SpecterDR. Usually, you’ll hear these criticisms of the optic:

1.) The weight is too much, or the optic is too heavy for what it is as a 4x optic.

2.) The mounting system is faulty, and the metallurgy of the ARMS levers leaves them subject to breaking.

3.) The external adjustments mean they’re exposed to environmental contaminants and that the optic can be “pushed” off zero when force is applied to the optic.

4.) Repeated manipulation of the lever to switch the optic between the 1x & 4x modes will result in your optic’s zero wandering and being lost.

5.) The eye relief is lacking and the eyebox is tight compared to 1-4x/6x/8x/10x LPVOs.

6.) The cost is high for the total package, with consideration to the above five points.

Every time the Elcan comes up in discussion, at least one of these are mentioned, but it’s usually multiple. Some of them are valid observations, some of them are total bullshit, most of them are said by people that haven’t used an Elcan extensively. I’ll tackle them from the angle of my personal experience before we widen the scope of input some.

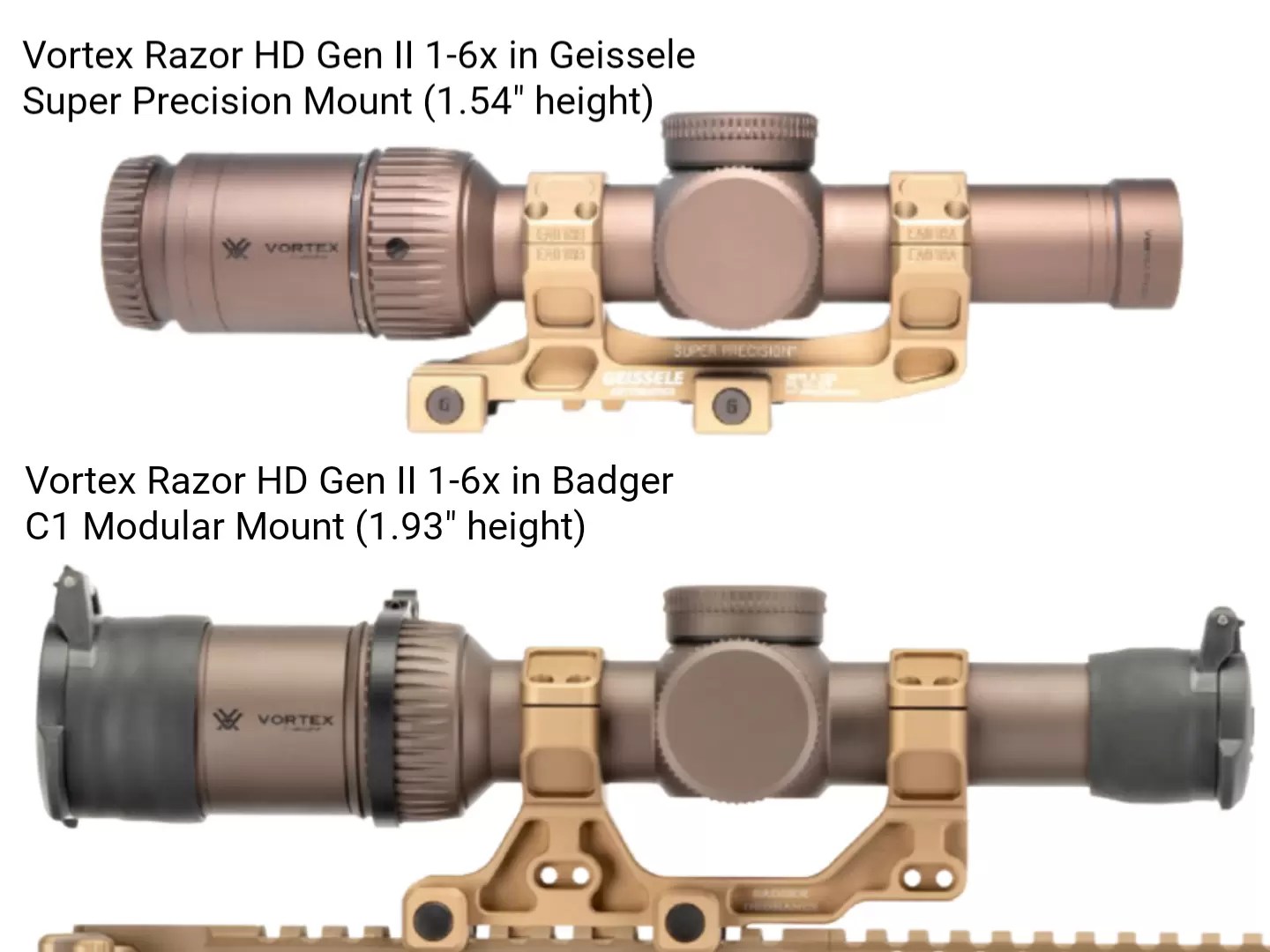

1.) Weight: While I acknowledged earlier that the Elcan is hefty but built tough for the smaller 4x optic that it is, and that I’m okay with it, this complaint usually comes with comparisons to LVPOs in the same or similar magnification ranges (1-4x & 1-6x), namely the Vortex Razor HD Gen II 1-6x.

First, as it pertains to 1-4x LPVOs: I don’t particularly pay much attention to these so I’m not sure which variety is in mind when the Elcan is compared to them. I understand the 1.1-4x S&B Short Dot (and Micro Dot before that) was THE SHIT back in the day 20 years ago, but nowadays they strike me as a wasted effort. We live in a 1-6x/8x/10x world as it pertains to LPVOs these days. If I’m going to make the effort of buying a longer optic that requires me to buy a separate mount for it to be leveled in, I’m going for an LPVO with a higher magnification limit on the top end, at least a 6x. This brings me to my next comparison, the Razor HD Gen II & Gen II-E.

In the world of LPVOs, the Vortex Razor HD Gen II (now Gen II-E) 1-6x scope is considered the gold standard, and to have set the bar where it currently sits as the rubric all likewise alternatives are compared to and measured against. A sleeper hit initially designed for competitive use, it saw unexpected appraisal from SOF units using them overseas in austere environments, and quickly gained notoriety in the tactical shooting circles for its rugged durability and reliability (sounds familiar right?) despite the leers of skeptics. However, not unlike the Elcan, despite that rugged reliability, it was also known for its weight.

When it was first released, the Razor HD Gen II 1-6x weighed 25.2oz. A later revision, now known as the Gen II-E, cut that weight down to 21.5oz. For its popularity among LPVO choices, especially for tactical or defensive rifles, and the aftermarket support available for it, we’ll take the Razor HD Gen II & II-E and pair them with the two most popular scope mounts available in 30mm to evaluate their weight all together: The Geissele Super Precision Mount (7.2oz), and the Badger Condition One (C1) Modular Mount (6.5oz):

Razor HD Gen II 1-6x + Geissele mount: 2.02lbs

Razor HD Gen II 1-6x + Badger C1: 1.98lbs.

Razor HD Gen II-E + Geissele mount: 1.79lbs

Razor HD Gen II-E + Badger C1: 1.75lbs

By comparison, the Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x weighs 1.45lbs.

So far all the complaints about the Elcan’s weight, it’s roughly over a quarter to half a pound lighter than any of the alternative combinations suggested, and almost half the length. For those that love to remind that “ounces equal pounds, and pounds equal pain,” this part of the math baked into their alternative suggestions seems to get overlooked.

Often you’ll hear the Razor’s weight cited, but not along with the weight of the required mount (unlike the Elcan, which has a self-contained mount). Sure, there are yet lighter mounts available, but the Geissele Super Precision Mount and Badger C1 Modular Mount are the two that are most often seen paired with the Razor HD Gen II, so that’s what I chose to focus on. In any case, you’ll still end up with an optic/mount combination that clocks in heavier than the Elcan on its own.

Bear in mind, my Elcan was chosen to sit on an already hefty HK416 upper, with a 10.4″ barrel. Were I selecting an optic for a 14.5-16″+ barreled AR URG (Upper Receiver Group), the floor would be an LPVO in the 1-6x range or greater. In fact, two of my other rifles, a 14.7″ barreled General Purpose Carbine, and an 18″ barreled SPR, both wear the newer Razor HD Gen III 1-10x. One sits in a Badger C1 mount, the other in a Geissele mount. The Razor HD Gen III 1-10x weighs 21.5oz just the same as the Gen II-E 1-6x, and is the same size (except for the 34mm tube), but we’re not going to get into the newer Gen III here.

The point here is that you have to pick the right tool for the job. The Elcan provided enough magnification for PID and ranged targets, and its durability, rugged reliability, and glass clarity within its size footprint and including its integrated mount on top of that outweighed (no pun intended) the weight concerns, for the weapon I was putting it on.

For the guys running to double check the weight specs of the Razor + Mount combinations stated above, that’s to say nothing of the added weight of an MRDS, by the way. While the Badger C1 was developed with a suite of attachments that accommodate a wide variety of accessories (to include offset and top mounted MRDS backup optic mounts), the Geissele mount was not.

However, the aftermarket did provide for this, notably in the form of the REPTILIA Corp ROF mounts made for the Geissele Super Precision Mounts to be used in conjunction with primarily the Razor HD Gen II 1-6x. They allow the user to mount a Trijicon RMR/SRO, Aimpoint Micro, or Leupold Delta Point Pro to the 1200 position (therefore adding further weight to the equation). We will delve into why later, but hold that thought for now.

2.) ARMS levers: I’ve been enjoying the fruits of the firearm industry tree for about 15 years now. In that time, I have owned Elcans (that only come with ARMS levers), I have owned an EOtech with ARMS levers (555, the AA battery version of the 553), and I have had friends that owned stuff with ARMS levers. I have heard all manner of shit said about ARMS levers: they break, they’re unreliable, the guy that made them wasn’t popular, etc. I have never had a problem with any of my ARMS-lever-equipped products. Not to say “It works for me” or suggest that I’ve barely used my stuff and therefore never gave it the opportunity to break or deny that it’s ever happened, but I personally do not know what you need to do to break an ARMS lever.

That being said, even if I managed such a feat, it wouldn’t be the end of the world. The ARMS MK-II levers, an upgrade allowing for adjustable tension (something the originals don’t provide for, which can be problematic with out of spec top rails) are compatible with the Elcan’s base, and can be upgraded at will by the end user.

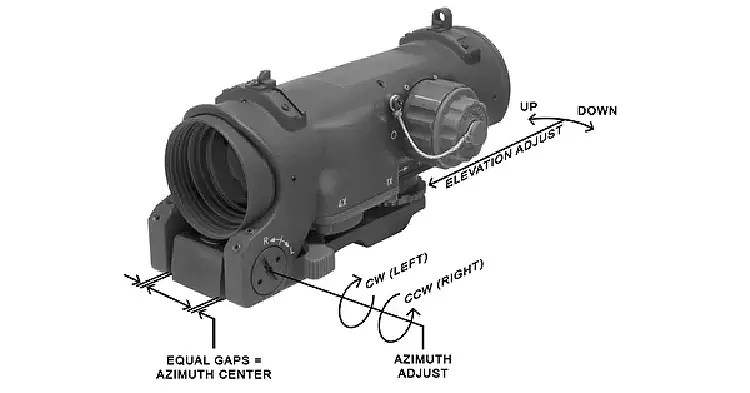

3.) External adjustments = External problems. This one comes with two parts. The first is that dust or debris can get into the “turrets” and that a click on the adjustment would potentially not equal an adjustment being dialed in. This is due in part to the way the Elcan is built: rather than the Windage and Elevation erectors being internal like a normal tube scope, they’re outside and under the main prism. When you dial in adjustments to either value, the whole body of the optic moves ever so slightly. As best I can tell, this is an unsubstantiated myth, as I’ve yet to run into anyone that actually had this problem rather than people saying “it could happen.”

The other part to this is, therefore, since the adjustments are external, applying pressure or weight or pushing on the body of the optic containing the prism could push the entire scope off of its zero. I’ve heard this same precaution said of Vortex’s UH-1 holo sight (an EOtech alternative), but I’ve gotta be honest: For all the awkward and odd positional shooting I’ve done, even the ones that forced me to mount a barricade and brace my rifle against it, NONE of it involved bracing or putting weight against the optic itself. I don’t know why you’d do that, and I can’t imagine a scenario where you’d be forced to that, therefore I don’t worry about it.

4.) “The Elcan unzeroes itself with repeated manipulation of the magnification setting lever.” This one’s straight-up bullshit. The magnification lever (and the lens assembly it manipulates) isn’t anywhere near the windage or elevation adjustment turrets. I’ve never seen it happen on the three models I’ve owned, and I went asking around to find someone who had. I will share my findings with you in a moment.

5.) Tight eyebox and eye relief. I’ve seen worse on other optics (looking at you ACOG, I’ll come back around to this), and I can get behind it just fine in kit and with my helmet on. It’s not as generous as 1-6x/8x/10x LPVOs (First and Second Focal Plane alike), but it’s not as bad as it’s made out to be.

6.) “For what it is, the price is too high compared to alternative options.” My first Elcan in 2012 cost me about $1700, and my second one in 2014 was $1800ish. By the time I had sold one and traded the other (basically due to peer pressure based on all of the above allegations), I watched as inflation brought the price north of $2000, and I said to myself well I guess I won’t be buying one of those again. Then, somehow, the price came back down to about $1650-1850, which is where it sits now (less any discount codes). I bought the one I have now used, LNIB, for $1400.

I’ve been told it’s dumb to pay Elcan money for an Elcan instead of a Razor HD Gen II 1-6x, which costs a bit less on its own. But once you factor in the cost of a quality mount, you’re back in that $1400+ neighborhood (barring any discount pricing). An ACOG with a top mounted RMR (the nearest adjacent 1x/4x combat optic) costs anywhere from $1450-2000+, depending on the model. Case in point, the Elcan’s price is right in the neighborhood for what it is, hardly outrageous once you take everything it offers into consideration, weighed against the alternatives.

Having addressed the most common critiques of the Elcan based on my personal experience, now I’m going to share some research I did for this article. I spoke to a seasoned combat veteran, and a respected member of the tactical shooting community on the LE/.mil side of the house. He served in the 75th Ranger Regiment (1st Bn) and the Asymmetric Warfare Group (AWG), with multiple tours of combat as a member of those organizations under his belt.

He did use an Elcan during his deployments, and afterward. I remembered his input when the topic had come up on Facebook in the past, and I remember him speaking fondly of the optic. I’m very fortunate to be able to call him a friend (we met back in 2014 at LVMPD SWAT school, where I had Elcan #2 on my carbine as a matter of fact), so I gave him a call and asked him about all those usual complaints regarding the Elcan. Here’s what he had to say:

“I deployed to Afghanistan with an Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x from 2008 to 2011. I had also T&E’d Elcans as part of AWG, prior to their adoption.

At first, I used an Aimpoint T1 + 3x Magnifier in the Korangal Valley. I found it unsatisfactory, and the 3x magnifier wasn’t working well, especially in the rain; it was eventually relegated to handheld monocular use.

Near simultaneously, we received three Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x sights in Jalalabad, in 2008. They were acquired by our organization as an external customer of the Crane selection. At one point I used the Elcan for 42 days straight in the Korangal Valley AO. I used the 4x setting especially for PID/observation.”

Things he had NO PROBLEMS with:

– ARMS levers

— “The tension on these NEVER loosened, although the optic was not repeatedly removed from the weapon, either. Once it was set and zeroed, it stayed on the weapon. The ARMS levers never broke, and I experienced NO functional problems with them.”

– Wandering zero via manipulation of magnification lever: “This is an ERRONEOUS RUMOR, and is ENTIRELY UNSUBSTANTIATED. I personally spent SIX (6) hours of attempting to replicate the problem in live fire at one of our ranges, and it could not be done.”

– “The glass never fogged in rain/cold.”

– “The external Windage and Elevation adjustments gave me NO problems, and I had NO problems with dust/debris interfering with click adjustment values, and there was plenty of moon dust around to be had.”

— “The optic was banged around A LOT: Dropped, Bumped, Thrown (into trucks, choppers, down a mountain, etc) on a daily basis.”

I asked him, “How often did you check zero after this daily abuse?”

“Every gunfight,” he told me with a laugh. “There was a point when I was in at least two gunfights a day. My Elcan’s zero never moved, for all the abuse I subjected it to.”

He echoed the notion that the Elcan is built like a tank: “The optic is not delicate, you could hammer a nail with it and not worry about damaging it or the glass. And it’s good quality glass, too. Makes for a big, clear sight picture, like looking at a TV screen.”

When I asked him about what drawbacks he found with the optic, he only had two minor complaints: One being the weight, that it’s heavy for what it is compared to an ACOG, and the other being that the size of optic (it’s almost as long as an upper receiver, and girthy in width) was cumbersome when racking the rifle while in transport.

All together, he had more positive things to say than bad, especially after the way it was used and bumped around in the environment he had it in. While this only testifies to a sample of one, and one that was used 10-13 years ago, he wasn’t the only guy on his team using it, and has stood by his remarks and evaluation of the optic in the years since. At the time, the Gen 3 had come out just in time for the SOPMOD Block II suite.

I did also obtain more recent feedback spanning a larger period of time. I spoke to another friend who served in AFSOC as a CCT. He also carried an Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x on his M4A1 on several deployments in Afghanistan, from 2009 to 2018. I asked him the same questions I posed to my 75/AWG friend, and he had this to say:

— Weight: While heavier than an ACOG, the capability of the Dual Role function outweighed this. Going from a 3-4m shot indoors to a 300-400m shot out the window of the same room and being able to do so with the flick of a lever was invaluable. Besides, having always had an M203 on the Elcan equipped M4A1, the Elcan’s weight was barely noticed.

— ARMS levers: Never had a problem with these breaking or losing tension, ever.

— External adjustments being exposed to the elements: Never not once was this ever a problem in all of his years of using the Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x overseas.

— Pushing on optic body throwing off zero: Not only did this never happen while using his Elcan, but he went on to say “I imagine the amount of torque you’d need to put that much pressure on the optic would affect any optic at that point.”

— Eye relief & Eyebox: On 4x engaging distant targets, it was no big deal. Using it on 1x as a CQB optic took some getting used to due to the eye relief (compared to an EOtech with unlimited eye relief), but when he did need a CQB optic, he actually preferred this and the more stable cheek weld over the Docter MRDS he had mounted on top initially (which other members of his team also used) that he zeroed at 25m for emergency use.

— Magnification lever manipulation resulting in zero loss: No, never not once. He actually laughed when I asked him this question, for the same reasons I mentioned above: “How would that even happen?!”

— How well did the zero hold up after impacts? What abuse was it subjected to? After the typical bumps and bangs you’d expect in transport in aircraft, trucks, armored vehicles, and helicopters, to include falling from a vehicle at one point, as well as the usual CQB instances of being hit into walls and doorframes just as often as any other optic might, the zero held up absolutely fine without moving. While on deployment, they would check zero often, multiple times a week even. At home, beyond the quarterly qualifications, the weapons remained in the armory and didn’t see so much use.

— Out of 80 users, all of whom were issued Elcan SpecterDRs AND EOtechs, the choice of which to use was left to the end user based on what they needed per mission requirements, at least 50 of them chose to use the Elcan, and did so happily. He didn’t recall anyone having any complaints to the point of condemning (like the internet tends to do), and he liked the optic so much that after he retired, he went and bought one for himself for his personal rifle. I reckon the cost (weighed against the alternatives) wasn’t much of a turn off.

So now you’ve got a ten year track record of Elcan SpectreDR 1-4x use on deployment (2008 to 2018) in combat, subjected to the conditions thereof, and the people that ACTUALLY USED THEM had positive remarks overall, and confidently dispelled many of the myths and negative hearsay regarding the optic.

I spoke to another friend who also has an impressive resume involving multiple deployments with the Marine Corps, and later as a PMC contractor with Blackwater, having embedded with the likes of DEA FAST teams for counter-narcotics and supply chain disruption missions in the same area. I had recently heard him say he wasn’t a fan of the Elcan, and I was curious why.

I asked him, and if he had ever used one during his deployments. While he hadn’t used one in any duty capacity, he did echo the earlier critiques pertaining to the weight, eyebox, and eye relief. There was yet one more complaint he had that I had not heard, but I can speak on from personal experience. He said, “the 400/500/600m stadia lines (on the BDC reticle) are too thick, they make it tough to see targets at range.”

Back in 2012 when I purchased my first Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x, its BDC reticle was calibrated for 7.62×51 (147gr from a 20″ AR-10 barrel). I bought it for my 16″ barreled LWRC REPR, which I had configured as more of a battle rifle. I still wanted to take advantage of the extended ballistic capability that the .308 round provides though, hence the 1x & 4x settings in one optic being preferable over just a red dot or holo sight.

At the time, most classes being offered that called for 7.62/.308 gas guns like the AR platform were precision shooting classes. You’d often see a lot of SASS (Semi Automatic Sniper System, like the M110) configurations at these events: 20″ barrels, high powered variable optics, big PRS-style fixed stocks. Long, heavy rifles not really ideal for the run and gun use that battle rifles were typically known for as primary weapons.

I wasn’t sure if I should just take my REPR to a typical carbine class that catered more to ARs chambered in 5.56, and just come up with a round count that accounted for the lesser capacity of the 7.62×51 magazines. Then, a few friends and I found out Chris Costa was offering a new class called 7.62 Heavy, which catered specifically to the 16-18″ barreled Battle Rifle & DMR configurations.

We signed up, and I brought my REPR + 7.62 calibrated Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x with me. The furthest we shot out to at that class was 400m, and I wielded my rifle and the Elcan’s BDC reticle to great effect. We were shooting at man-sized steel targets, and the holds on the reticle were so precise, that all I had to account for was windage when addressing targets further away. I was able to run through the target relay so fast, that I was considered one of the better shooters in the class, and selected to be a team leader for later exercises.

Case in point: The stadia lines on the Elcan’s BDC did not at all occlude my vision or sight picture, nor did they prevent me from acquiring one at 400m. While I haven’t yet had the opportunity to use it at further distances, I would not feel discouraged from making the attempt.

In closing, this friend said, “My favorite 4x optic for size, weight, and performance is still the ACOG.”

Which brings us to the next section of this epic…

SECTION 3: Elcan vs. ACOG vs. 3x Magnifier

Another question I’ve been asked regarding my preference for the Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x is “Why not use an ACOG? It’s lighter weight and just as durable.”

Before I answer that question, let’s take a brief glance at the ACOG’s history, and its nearest adjacent configuration to the Elcan (as I use it at least).

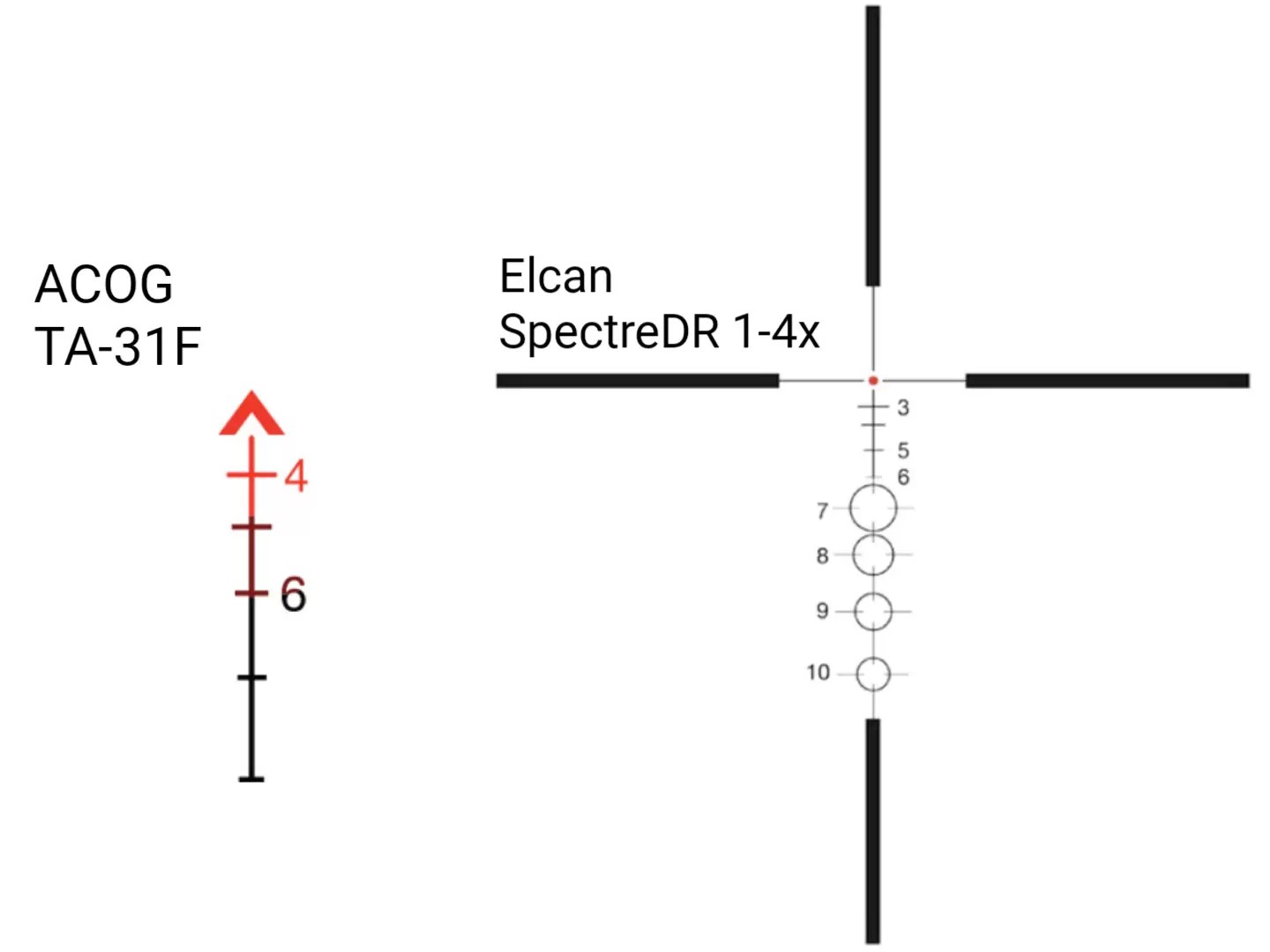

The Trijicon ACOG is as old as I am. It was first introduced to the world in 1987, in the form of the TA01. This was the first of the venerable and renowned 4×32 models that come to mind when one thinks “ACOG.” While they were first adopted into military service in bulk via a 1995 procurement by SOCOM for 12,000 units, the ACOG’s popularity exploded and its reputation was truly cemented in 2004, when the US Marine Corps purchased 104,000 of them at once, making the TA-31F 4×32 the official Rifle Combat Optic (RCO) of the Marine Corps. From there, it would be seen on every standard-issue M16A4 and M4A1 issued to every Rifleman and would go on to be known as the face and poster child of magnified optics throughout the GWOT.

Starting in 2006, Trijicon began to offer the 4×32 ACOG with a Docter MRDS piggyback mounted on top. In 2009, Trijicon released the RMR (now famous for its application as a pistol-mounted optic), which replaced the Docter MRDS going forward. For the purposes of this article, this is the permutation of the ACOG we’ll be focusing on.

There are a couple of important details about the ACOG to point out upfront. It’s a fixed 4x optic, meaning there’s no variable magnification feature. It utilizes a combination of tritium and a fiber optic rod to keep the reticle illuminated day or night, so it uses no batteries (although there are battery-powered versions of the ACOG also). In this configuration that includes the RMR, the cost is comparable to that of the Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x, in the $1750 range (with an MSRP of $2310).

Now let’s compare the 4×32 ACOG to the Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x on 4x mode, point for point.

Durability & Reliability:

Nothing much to say here, both optics are equally matched as per those that have used them downrange in austere environments.

Size & Weight:

The Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x weighs 1.45lbs, and is 6″ long by 2.9″ wide, and 3″ tall. The 4×32 TA-31F w/ RMR weighs just under a pound, coming in at a factory weight of 15.1oz while using the standard TA51 mount. It is 5.8″ long by 2″ wide with a height of 2.5″. Both being combat optics of similar size using an integral mount, the point obviously goes to the ACOG in terms of weight, having the smaller form factor and simpler construction.

Eyebox & Eye relief:

All 4×32 ACOGs have an eye relief of 1.5″, compared to the 2.75″ eye relief of the Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x. It’s one of the most common critiques of the ACOG, because that’s really tight, and necessitated a shooting posture that became known as “nose to charging handle” or “N2CH” for short. Barring any aftermarket mounts that situate the optic even more rearset than it would be normally, this meant that the tip of your nose needed to be touching the AR’s charging handle (or just about) to acquire the proper eye relief to obtain a sight picture. Like I said, it’s tight.

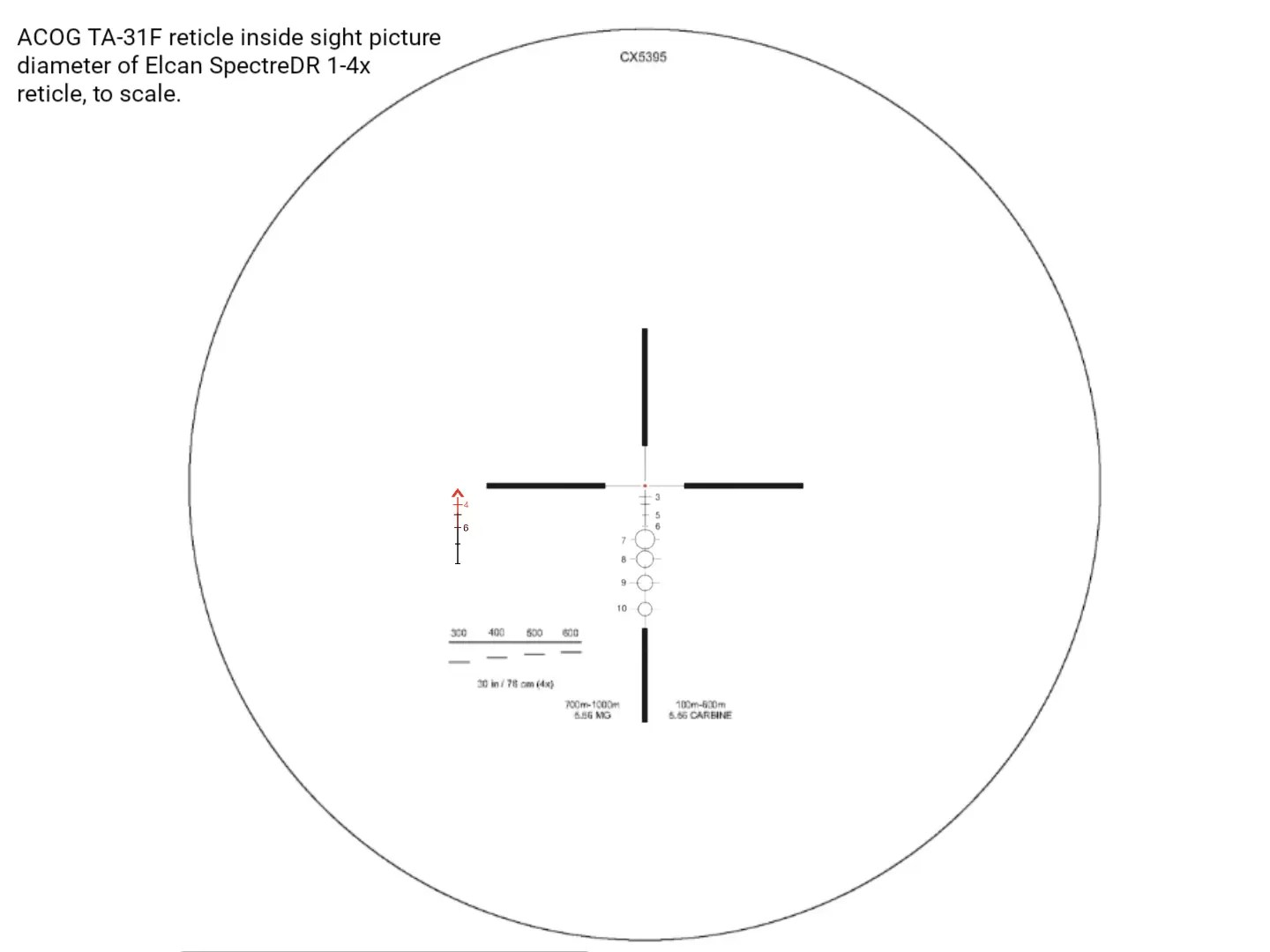

I do own a TA-31F, though it doesn’t much get used. When I compared the ACOG’s eyebox (how off-center your pupil can be from the ocular lens while still able to retain a proper sight picture) to the Elcan’s, they seemed about the same to my eye. Where both optics have a 32mm objective, the Elcan’s exit pupil is 8mm, and the ACOG’s is 8.13mm, so it’s fair to say their eye boxes are comparable.

Having looked through both, however, I can say with confidence that the Elcan’s eye relief and eyebox are all together more generous than the ACOG’s, even if only by a small measure. So that’s one thing the Elcan’s got over the ACOG when you’re comparing the two as 4x combat optics.

Clarity and sight picture:

The Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x, when on 4x, has a Field Of View (FOV) of 34.2ft @ 100 yards, or 11.4m @ 100m, 6.5-degrees overall. The 4×32 ACOG has a FOV of 36.8ft @ 100 yards, or 12.27m @ 100m, 7-degrees overall. Between the two, you’re splitting hairs in terms of FOV and sight clarity, as both use quality glass. You just need to get closer to the ACOG to see it.

Reticle & Ranging:

Here’s where things start to functionally deviate. While Trijicon offers a variety of reticles across their 4×32 line, the chevron BDC reticle pictured above is the most common. As you can see, it’s a simple stem with stadia lines marking the elevation holds out to the respective distances x100m. The upper tip of the chevron is where it’s meant to be zeroed at 100m, the inner apex is the 200m hold, and the base of the chevron’s legs is the 300m hold. Starting at 300m at the widest point on the chevron, and narrowing down as distance increases out to 800m, the stadia lines are roughly the width of a man-sized target (19″) at the numbered distances given, which is meant to assist in ranging targets at UKDs (unknown distances). That’s really all you get out of the ACOG reticle above.

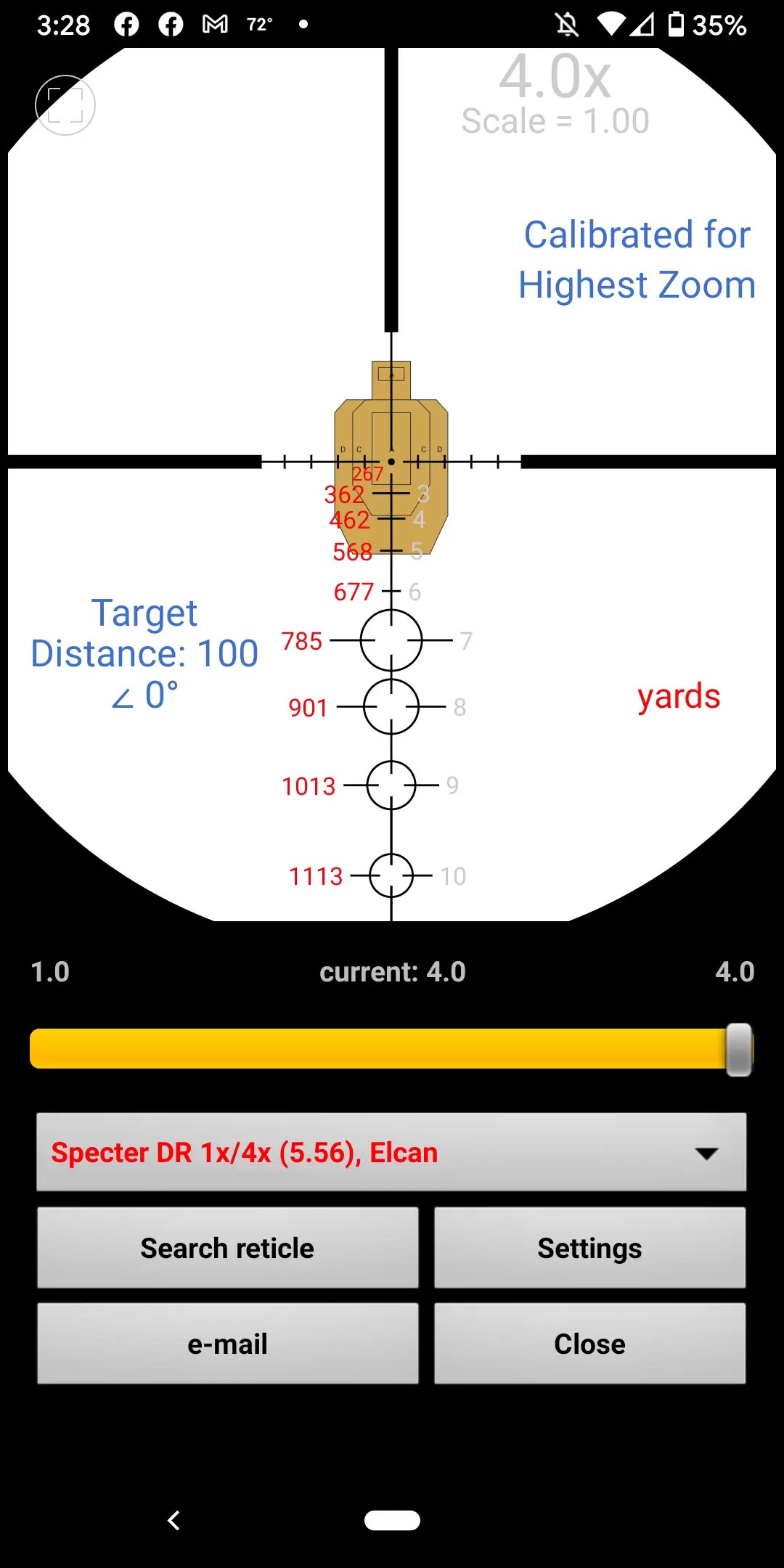

The Elcan reticle offers more information. While also zeroed on 4x at 100m (wherein the central dot is 1.5MOA square on that magnification setting), with stadia lines also approximating the width of a man-size target at each respective distance out to 600m, the Elcan’s reticle goes further. From 700 to 1000m, the stadia are replaced by circles, for use with LMGs like the M249 SAW. As I understand it, the circles are sized just so that a man-sized target would fit inside from head to toe at the labeled distance. I suppose you could use these to dope a target at those distances with a carbine, but I’m not sure why you’d want to at 4x magnification. I wouldn’t.

While the Elcan’s 5.56 BDC reticle is calibrated for 62gr M855 out of a 16″ barrel, mine is zeroed with Barnes VOR-TX 70gr TSX. Flying from the 10.4″ barrel at that projectile weight, I lucked out: the drop rate closely matches the BDC calibration of the reticle, near enough that I wouldn’t be terribly far off using those holds to engage distant targets.

Going further, there’s yet more information provided by the Elcan reticle. Not only does it provide ranging capability in width via the stadia lines, it also does this for height as well. In the lower left-hand corner of the reticle, you’ll see the second ranging reticle, and how it denotes 30″ at 300-600m. The bottom of the reticle tells you what caliber the BDC is calibrated for.

So between the ACOG and Elcan as far as 4x reticles go, I find the Elcan has more to offer in the form of information provided by the reticle.

Zeroing:

For all three of my Elcans, zeroing was a cakewalk. Shoot group, dial windage, and elevation adjustments, confirm, call it a day. The 1/2MOA @ 100m click values might seem a bit much compared to 1/4MOA or .1MRAD, but they make it easy without too much approximation (provided you’re shooting good ammo out of a good barrel).

The ACOG, on the other hand, is a fucking bitch to zero in my experience. I asked a few people about this just to make sure I’m not crazy, and they confirmed that what I’m about to tell you is a known thing. Because the windage & elevation turrets are so finicky (and susceptible to dust/debris throwing off the 1/3MOA click values, I’m told), the springs inside don’t always move the reticle inside the prism as you dial adjustments in. They’d get stuck at first before the erectors moved. It’s not uncommon to hear about people having to chase their zero by over adjusting and then having to dial back half. One trick to remedy this was to beat on the turrets with the base of a magazine to free up the springs and get whatever adjustment you dialed in to set. I’ve had to do that myself. It’s annoying, which is why my ACOG isn’t even mounted to a rifle right now. Who the fuck wants to put up with that?

Multi-role function:

We’ve compared the two optics point for point as 4x combat optics. Now let’s look at how they function from close to mid range. This is where things get more sophisticated.

Let’s go back to the combination ACOG & Docter MRDS, and later the RMR. There was a reason this configuration was dreamt up, and that’s because the ACOG was lacking in close quarters. While the BAC (Bindon Aiming Concept, using the ACOG with both eyes open not unlike a red dot or holo sight) was a thing by the time the ACOG was a standard issue item in the US military, it still sucked in the heat of close quarters battle because of the ACOG’s aforementioned tight eye relief. So to remedy this, an MRDS was added on top of the ACOG. Raising one’s head and shifting from a cheek weld to a chin weld took you from fixed 4x magnification with its tight eye relief, to a 1x red dot with unlimited eye relief. Easy peasy.

Now mind you, while offset and top or “1200” mounted MRDS over magnified optics are still a thing today, there are additional applications today than there were initially (we’ll revisit that later on). The problem that the Docter and RMR sights atop ACOG configuration was meant to solve was to provide a rapid CQB sighting system that wasn’t restricted by eye relief, and it did that. The RMR that sits on top is battery-powered and has a 3.25MOA dot. It provided 1x on top of 4x capability in one package, but not without a caveat.

The thing about it was it seemed “weird” to go to a chin weld to utilize the MRDS at a time when the majority had gotten used to retaining a cheek weld while aiming down their sights with the advent of the flat top upper receiver, even though utilizing a chin weld to aim through a carry handle mounted optic wasn’t too far distant in the past. As time often tells, however, what’s old is new…

At this point in time, LPVOs, as we know them today (those that bottom out at 1x and with a generous eyebox and eye relief), hadn’t come into being. The technology hadn’t yet matured to the point it’s at now. For the guys that wanted to stay with the preferred cheek weld to aim down their sights, and also didn’t want to cant or rotate their weapons at a 45-degree angle to use an offset mounted 1x optic they felt they’d be using more often, they were left with a choice: Either/Or between 1x and 4x, or 1x with a rear-mounted 3x magnifier.

With either of the 1x choices, a 3x magnifier could be used for the same purpose and functions the ACOG provided, but this came with a few drawbacks of its own: the size of the reticle was increased 3x, which could occlude targets further out as previously touched on. Weight was on par with the Elcan and ACOG (an EOtech EXPS3-0 + G33 3x magnifier weighs 1.4lbs, and an Aimpoint T1 w/ Aimpoint 3x magnifier + mounts weighs just under a pound at 15 ounces and change), but for less magnification on top of the magnified reticle. Pair that with having to utilize your support hand to move the magnifier into place behind the optic or out of its way, and it just seemed all together to be more trouble than it was worth compared to lifting one’s head a bit to use the piggybacked MRDS on the ACOG.

So, the options were limited: Aimpoint or EOtech on the 1x side (either of which could be used with a cumbersome 3x magnifier), and the ACOG on the 4x side. You could have your cheek weld with no magnification, or some clunky magnification with extra steps, or you could have a cheek weld for your 4x magnification, and a chin weld for 1x. Meh.

Enter the Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x in 2005.

When it first came out, the novel thing about the Elcan (besides all the aforementioned advantages over the ACOG) was that you got to have your cake and eat it too. The DR in SpecterDR stands for Dual Role. In one combat optic-sized unit, you got both 1x & 4x, AND you got to retain your cheek weld either way. So there’s your dual roles: CQB, and Marksman-ish. Eureka! Well, kinda.

Remember how the MRDS was added to the ACOG because it sucked having to use the BAC with such short eye relief in close quarters? Well, while we established earlier that the Elcan’s eye relief is better than the ACOG’s, it’s still tight on its own. Speaking from personal experience, having to contend with the Elcan’s eye relief on 1x, while trying to use it as a 1x optic, while kitted up, kinda sucks. Especially compared to having a 1x optic with unlimited eye relief.

[Note that ARMS levers switched sides]

The engineers over at Elcan were aware of this by 2006, the same year Trijicon first released the ACOG with a piggybacked Docter MRDS. Part of the upgrades for the Gen 2 version of the Elcan (released that same year) was the addition of drilled and tapped holes on top of the optic, in order to install the screws for a saddle mount upon which to mount an MRDS. This feature carried over into Gen 3 when it released in 2007. So at this point in time, the Elcan enters the GWOT, and could do everything the ACOG could, but better, and then some.

Truly, given my intended use for the Elcan as an adjacent (albeit improved) alternative to the ACOG, I would have been better off using a different Elcan: The SpectreOS4x. This was a scaled-back version of the SpecterDR with a fixed 4x magnification, and no ability to switch to 1x. This came with a couple of reductive benefits: While the same size dimensionally, it was lighter weight (1.08lbs vs the SpecterDR’s 1.45lbs), and it also cost less ($1250). Beyond that, the lack of fixed BUIS, and a slightly tweaked reticle, it was functionally the same as the SpecterDR 1-4x, meaning the MRDS saddle mount compatibility was retained. Alas, this was a missed opportunity: by the time I purchased my third Elcan for my HK416 upper, the SpectreOS4x had been discontinued. C’est la vie.

All of this to say, thus answers the question of “Why not just use an ACOG + RMR, if you’re only using the Elcan on 4x?” Because as far as I’m concerned, it’s a better ACOG, functionally speaking. Not to suggest the ACOG can’t do the job (it can, and has been), but in exchange for some added weight, the Elcan provides a better reticle, and a better eye relief & eyebox, where clarity, durability, and reliability are tied between the two. The Elcan is also much more cooperative when it comes to zeroing, too. While we’re at it, although comparably priced, it’s also lighter weight than a Vortex Razor HD Gen II 1-6x + mount, in a more compact package. Moving right along…

SECTION 4: Closed Quarters Optics

While I have seen a good few pictures over the years of the older Gen 2s and later Gen 3 Elcans with 1200 saddle mounted MRDS optics up top in the cloner boi circles, I don’t personally know anyone that used one overseas. That being said, I saw the value of having the offset MRDS after my own CQB training experiences I wrote about in my In4med-16 article here on Breach-Bang-Clear.

So, I had a reason. I had a spare Aimpoint ACRO laying around, and I knew the 1200 saddle mounted MRDS on an Elcan was a thing. I just needed to fill the gap between both optics by finding a saddle mount made for the Elcan that I could mount an ACRO to. Fortunately, I knew exactly who to ask: Enter REPTILIA Corp.

Between Eric Burt & Nick Booras over at REPTILIA Corp, they both share a history of working for companies in the industry that possess an avant garde design philosophy, and it shows in their resumes: While both have worked for Magpul, Eric worked for AAC (he was working at Crye Precision when I first met him), and Nick previously worked for SilencerCo and Radian Weapons. The forward thinking tenacity these five companies share in their approach to product development carried over to REPTILIA with Eric & Nick when they started it, and it shows in numerous products they’ve brought to market since then.

Earlier, I mentioned the ROF, which comes in both 45 and 90 degree variants. These are drop-in components developed to work with the 30 & 34mm Geissele Super Precision Mounts. They allow for the end user (most of whom are initially from domestic and foreign special military units who request these items of REPTILIA) to mount a variety of open emitter MRDS optics to the top of their LPVO optics at 1200. I typically see the 90-degree option more often than the 45-degree, and I can make an educated guess as to why. But we’re not there yet.

Among their other optic mount offerings are their saddle mounts. Having seen how quickly REPTILIA could move a product from concept to prototype to production model, it stood to reason that REPTILIA had the wherewithal and capability to design and produce a saddle mount for the Elcan to which I could seat this extra ACRO I had laying around. When I approached Nick in regards, it turned out they had already had the idea, and had in fact designed two models: one for the Aimpoint ACRO, and another for the Aimpoint T2.

Besides the manufacturer and that they’re both red dot sights with unlimited eye relief, one important thing that these two optics share in common is that they’re what’s considered closed emitter optics. What this means is that all the mechanical components of the optic– especially those responsible for projecting the reticle onto the glass– are contained entirely within the optic’s chassis, or hull.

The greatest advantage to this is that the emitter is enclosed and therefore protected from the elements, or any dust, debris, etc. While it’s not a huge problem with open emitter MRDS like the Docter sight, the RMR, or the Leupold Delta Point Pro, it is a possibility that if the optic (and the weapon attached to it, obviously) were to be dropped or submerged in water, dirt, or mud, the emitter (the part that projects the dot reticle onto the glass), being “open” or exposed to the world beyond the optic’s body by virtue of its design, could become occluded. This could potentially prevent the optic from properly functioning via whatever debris blocking the emitter, and therefore prevent the user from aiming properly since they’d either have no dot or a misshapen dot.

So you can see the appeal to having a closed emitter optic wherever possible. Aimpoint has only ever dealt in closed emitter optics, so when they started making smaller versions, it made sense to see them pop up in places where previously there were only ever open emitter options; rifles and pistols alike, in the case of the T2 & P1 ACRO.

So I had this spare ACRO laying around, and I didn’t want a second RDS-equipped pistol (I already had the first ACRO on my Glock 19X). I had an idea to park this one on top of my Elcan, since I knew I wanted an MRDS on that rifle, I just needed a way to do it. I looked at the available MRDS saddle mounts made for the Elcan: they were either dedicated to RMR mounting, or a straight up pic rail, which would necessitate a second intermediary mount. This would unnecessarily add height to the backup MRDS and introduce further tolerance stacking, and I didn’t want that.

When REPTILIA developed the Elcan saddle mount, the original idea was to allow for the use of an MRDS to supplement the Elcans that were being used as MGOs (machinegun optics). The T2 Micro is still Aimpoint’s premier optic used on rifles in a backup fashion by wide margin, and this is why you only see this version listed on the REPTILIA site, and on 1.5-6x Elcans mounted on top of belt fed LMGs: it’s what’s in use and what’s in armories for .gov customers using Elcans the most, so they leaned into producing it in quantity. It’s a purpose built direct mount; the T2 mates directly to the saddle, so there’s no added height beyond what’s necessary.

Before REPTILIA, there was no way to mount a closed emitter RDS onto a combat optic. Both the ACOG and Elcan only ever catered to the open emitter Docter and RMR sights. Riding on top of the Elcan, the closed emitter optics provide the same function as a rapid transition unlimited eye relief 1x optic, with better protection. It lends itself well to the job of a machinegunner, just as well as it does an assaulter in CQB. This is one reason the ACRO rides atop my 1-4x Elcan.

While the 1-4x Elcan model could accommodate the T2 saddle seen pictured on the 1.5-6x model, I didn’t have a T2. When I brought it up, Nick showed me what each model looked like “in the white,” prior to anodizing, and told me only one ACRO saddle prototype had been made up to that point, and distributed for T&E to end users overseas. I asked what it would take to get one myself, and although we discussed the details, the COVID-19 pandemic fucked that whole plan up. That’s how I ended up with the ACRO on a Rukh offset mount, as an alternative.

But then, one day in December, a box arrived before Christmas. When I opened it, my eyes lit up. A tan anodized REPTILIA saddle, made for the ACRO, a direct mount just like the T2 version, was inside. As I understand it, only two (2) ACRO version REPTILIA saddles for the Elcan SpecterDR exist.

“Why did you switch your ACRO from the offset mount to 1200 on the Elcan?”

So glad you asked. Besides keeping my rifle upright while using the ACRO, and resuming a normal posture with the weapon in a CQB setting, there’s another reason I wanted to set it up that way. It’s in light of a more recent concern that’s come up in the last few years, and one I would *also* want to keep my rifle situated upright for: Passive Aiming.

SECTION 5: Heads up, Lights out.

Finally. Here we are. The original concept for this article that got the ball rolling before it grew and evolved into the monster it became between the first keystroke and this section. Everything before has led to this. If you made it this far, you can see the light at the end of the tunnel just like I did when I started writing this paragraph. Let’s get to it.

While I briefly covered it in my previous article, let’s review: Passive Aiming is when you aim through your optic while wearing night vision, in order to avoid telegraphing your position (to adversaries also equipped with night vision) by using the IR lasers & illuminators you’d normally use to aim with, which anyone with night vision can see. You’re lining up your night vision behind your optic, while lining up your optic’s reticle with your intended target. If you’ve ever seen a red dot or holo sight marketed with night vision settings, this is why: you’re basically dialing down the intensity of the reticle so it doesn’t bloom and become a giant bright blur under night vision.

Passive Aiming became increasingly of interest as the proliferation of night vision systems also increased world-wide, by end-users foreign and domestic, civilian and military alike. When used against cave dwellers and other nefarious insurgents that lack such a capability, it dramatically stacks the deck in favor of those that do have it. When everyone can do it, well, the playing field becomes more level and less stealthy.

In terms of foreign countries that pose a potential military threat to our own, the phrase that you may have heard that’s been used to describe this in industry literature is “Near Peer.” Simply put, it refers to militaries belonging to foreign countries (or “peers”) that nearly match the US military in warfighting technology and capability, or would potentially be a considerable adversary in war. In this particular context, it refers to the small arms and related technology at the infantry level: Weapons & ammo, body armor, night vision, etc.

The last two decades of GWOT taught our military and government leaders a lesson or two about preparing to fight yesterday’s war, as they’d tend to do in the past. Now they look ahead, to who we might end up fighting in the future. Given the landscape, the options are less resembling guerrilla irregulars, and more uniformed military Near Peer threats.

As it dawned on our military that we could be facing adversaries that possess technology that rivals our own, that had to be accounted for by adapting technique. This applies just as well to LE; there’s nothing stopping perps from getting night vision and using it to attack or surveil innocent people or police officers themselves, and it applies to civilians also; without rule of law, when every man is out for himself and his own, those are the teams they’re playing on. If they’ve got night vision, they have an advantage over everyone else, except those that also have it. In either case (LE, Mil, and Citizen), nobody wants to prematurely compromise themselves.

As it pertains to Night Vision, that’s where Passive Aiming comes into play: you can still see, you can still aim, you’re just not telling the other team where you are or what direction you’re looking in. This requires some tweaks to the way we set up our night fighting rifles, but nothing drastic.

Passive Aiming capability is a simple formula. You basically just need a taller height mount for an optic that’s conducive to doing it. This is where the red dot and holo sight optics shine, since you’re essentially aiming through it as you normally would. You could passively aim through a magnified optic that’s set in a 1.93″ or higher mount, but now you’re contending not only with the standoff distance of your night vision behind the optic but you’re constrained to the eye relief and eye box of that magnified optic THROUGH your night vision and keeping it lined up behind the optic properly.

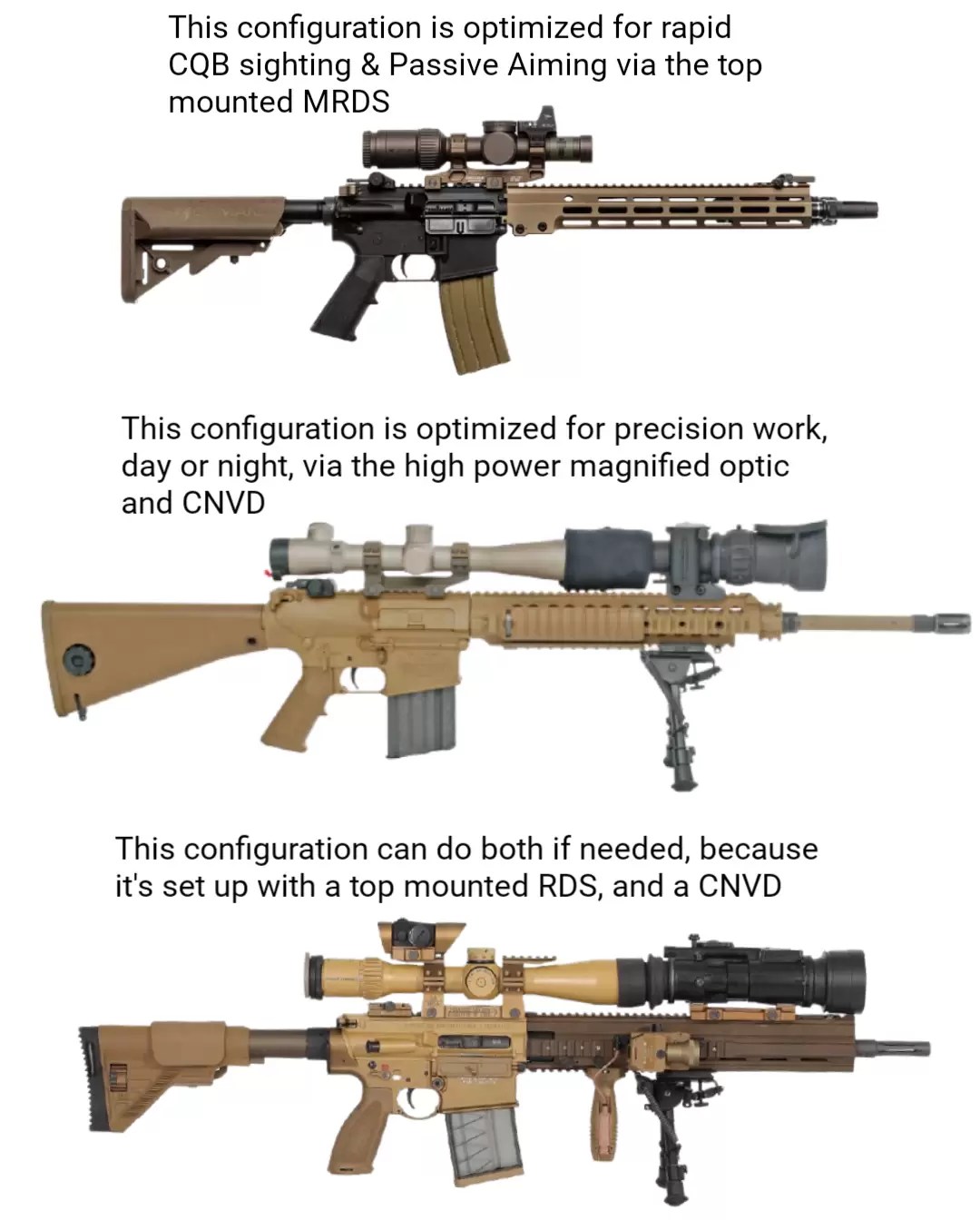

For what’s primarily intended as a CQB and urban fighting method, that’s more trouble than it’s worth (to me at least). This is why I never put the Elcan itself on a riser to attempt using it passively on 1x (despite the fact that the reticle illumination is NV compatible). If night vision + magnified optic for a precision rifle is what you’re after, we have CNVDs (Clip-on Night Vision Devices) for that. They attach to the top rail of the rifle’s handguard in front of the optic, and that’s a whole different ball of wax, neither here nor there. But those rifles sometimes also have a 1200 or offset mounted MRDS for CQB and Passive Aiming purposes anyway, in cases where the designated marksman needs to shift gears for indoor work when called upon.

But wait, doesn’t a taller mount mean we’re getting away from the cheek weld and venturing back into chin weld territory? Indeed it does. As I said earlier, what’s old is new. But this time, for a different purpose. Let’s look at why we’d use a chin weld and how the application has changed over the years up to now.

Originally there was no flat top upper receiver. From the late 50s with the advent of the AR-10, through Vietnam in the 60s & 70s, and through the end of the Cold War and into the Gulf War in the 80s and 90s, optics were mounted to the AR platform’s fixed carry handle, because that was all it had. So for a long time, the chin weld was the thing to do if you wanted to use a sighting system other than iron sights. It wasn’t until the Mid 90s that flat top upper receivers and backup iron sights entered the mix, where you could now have a sighting system capability greater than the iron sights, but ALSO retain the much more stable and ergonomically pleasing cheek weld we’ve all been accustomed to.

For the next 10-15 years, that’s how things would stay for the most part, and the cheek weld was where it was at on the commercial end-user side of things. On the .mil side, SOF had continued using carry handle mounts (even the detachable top rail mounted variety), risers, or a combination of those in lieu of what would later become standard offerings of taller mounts by the industry, in conjunction with the aforementioned ACOG, 1-4x LPVOs and earlier model EOtechs.

At the time (back in the Mid 90s into the early 2000s) there were two primary reasons for this. One was so the S&B 1.1-4x LPVO would clear the height of the PEQ-2 laser when on 1.1x so the guys could have a clear sight picture when using said optic in lieu of a red dot sight. The other reason was for Chem/Bio concerns (due to the Gulf War) where a taller mount makes it easier to square up behind the optic and get a sight picture with a quasi-chin weld while wearing MOPP gear.

I encountered the latter conundrum of aiming in a gas mask during my first run through DARC back in 2011. All I had was my flat top rail mounted EOtech 555. Kicking the collapsible stock out to its maximum length helped get the optic out there and easier to get behind, but I quickly saw the utility something like a LaRue 5/8″ riser (which was developed back in the early 2000s based on requests and input provided by SOF personnel while they were improvising with an optic on a detachable carry handle on a riser on a flat top back in the day) would have provided.

By the mid-2000s, the chin weld returned for the aforementioned RMR over the ACOG & Elcan for rapid CQB sighting less tight eye relief. So by this point we’ve gone from it being the only option, to clearing accessory height and gas mask use, to quick heads up CQB backup optic use. However, given mainstream tech upgrades over time (niche applications notwithstanding), the cheek weld remained the preference.

In the Mid 2010s or thereabouts, the chin weld would return to prominence in the form of purpose-built scope mounts dedicated for .mil and LE tac team assaulters using LPVOs as their primary rifle optics, usually accompanied by an offset red dot sight like an RMR or Aimpoint Micro. This is also the time where LPVOs (the Vortex Razor HD Gen II 1-6x among them especially) really matured technologically and came into vogue, taking their place as the go-to optic for general purpose carbines. This is further corroborated by the military’s adoption of LPVOs as standard issue optics for certain infantry weapons. Reason being, not unlike what the Elcan first sought to accomplish, it provides a wider tasking capability for the optics package and the rifles upon which they’re situated, from close range out to distance.

Right around now is when we started seeing more mounts in the 1.93″+ height range offered by a variety of manufacturers (where previously it had only been LaRue Tactical with the 1.93″, or the 1.5″ SPR mount on a riser). The reason for the tall mounts (“tallboys,” as they’re colloquially referred to) was because they make it easier for the assaulter to acquire a sight picture while contending with eye relief in full kit (CBRNE gear or not) with the trade-off of being less optimal for prone, though this wasn’t something an assaulter was expected to have to do often in CQB. The other reason was, by now, when CNVDs had come into play, the 2.04″ mount height gave users the option of using a tallboy mount, and with the simple addition of a half-inch riser to a CNVD with an output screen aligned for 1.54″ height scopes, this raised the CNVD up to its proper position in front of the day optic in a 2.04″ mount.

Meanwhile, around the same time in the early to mid-2010s, red dot sights paired with magnifiers likewise situated on risers or dedicated tall mounts (like the EOtech XPS3-0 + G33 Magnifier on a Wilcox mount) were also coming back into popularity, and therefore bringing the chin weld back into practice with them. But at this point in time, it wasn’t because of a carry handle mounted optic, or clearing a laser, or MOPP gear, or a quickly acquired CQB optic or LPVO. This time, it was Passive Aiming, thus bringing us full circle into the current era.

I’ve already explained what passive aiming is and why it’s relevant with regard to near-peer concerns. In this context, the taller mounts make it easier and faster to line up the optic in front of helmet-mounted night vision, while ensuring there’s enough clearance and stand off from the night vision to do so. Trying to do so with a lower 1/3rd or standard height mount wouldn’t work (I’d know, I tried). Because of the angle of the night vision relative to the wearer’s head, and further in relation to the rifle, the optic on top of it, and height of the rifle when shouldered, if you tried to do passive aiming with a lesser height mount, the night vision device would crash into the optic before you were able to line up behind it proper. Therefore, the tall mount or 1200 mount over a magnified optic is the only way to do this. If a lower 1/3rd cowitness mount is too short, how tall does the mount need to be?

Let’s take a sec to look at how the taller mounts, meant to facilitate passive aiming nowadays, compare to the carry handle mounted optics of old. Above you can see three mounting solutions: a fixed carry handle with an ARMS rail, a Unity FAST mount, and a Knight’s Armament Skyscraper mount, all fitted with Aimpoints. As you can see, they all arrive at the same height over bore, or similar nearabouts, and they all require a chin weld to use. Once again: what’s old is new.

So how does my Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x + ACRO compare? Let’s look at the numbers for height over bore (mounts including the red dot optics):

Aimpoint T2 + KAC Skyscraper: 3.53″

Aimpoint CompM5 or Vortex Sparc II + Unity FAST: 3.66″

Aimpoint PRO + Carry Handle: 4.0″

Trijicon RMR over ACOG: 4.25″

Trijicon RMR over Geissele Mount (1.54″ standard height): 4.25″

Aimpoint ACRO over Elcan: 4.25″

When using an HK416 upper, add 3/8″ (.375″) to factor in the added height of its top rail over a standard AR-15 upper receiver. This leaves me with an ACRO height over bore of 4.625″

As you can see, while the ACRO mounted to my Elcan via the REPTILIA Corp saddle mount is the tallest of the bunch (once it’s on the HK416’s raised height upper), it’s not at all incomparable, coming in at only a smidge over a half-inch taller than the RMR mounted over the ACOG or the Geissele mount using an ROF-90. Rather, it’s right in the neighborhood, and therefore very conducive to passive aiming with night vision. Now that we’ve finally covered everything that went into how I got to picking the Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x and parking an Aimpoint P1 ACRO on top of it, I can finally talk about what it was like using it as intended.

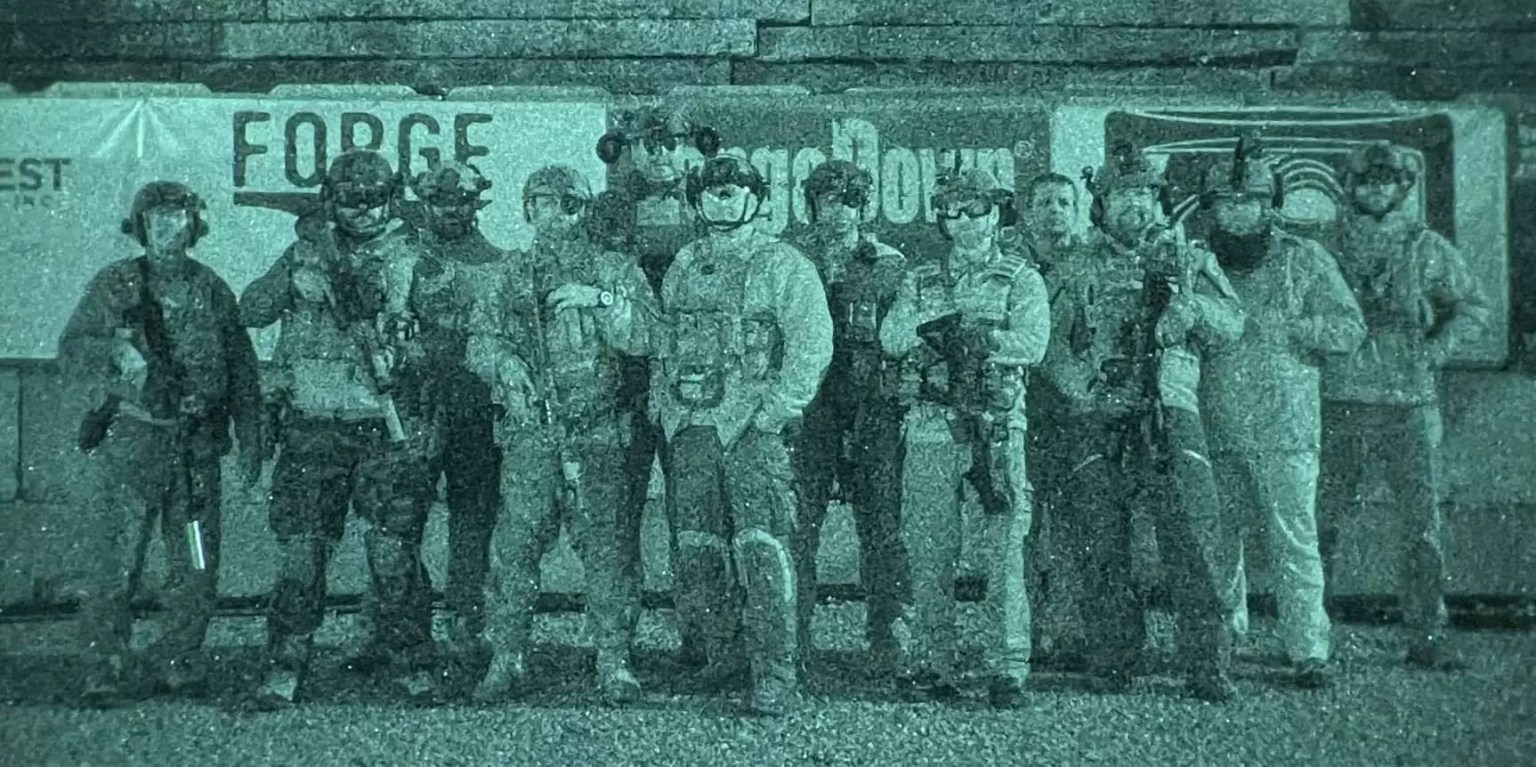

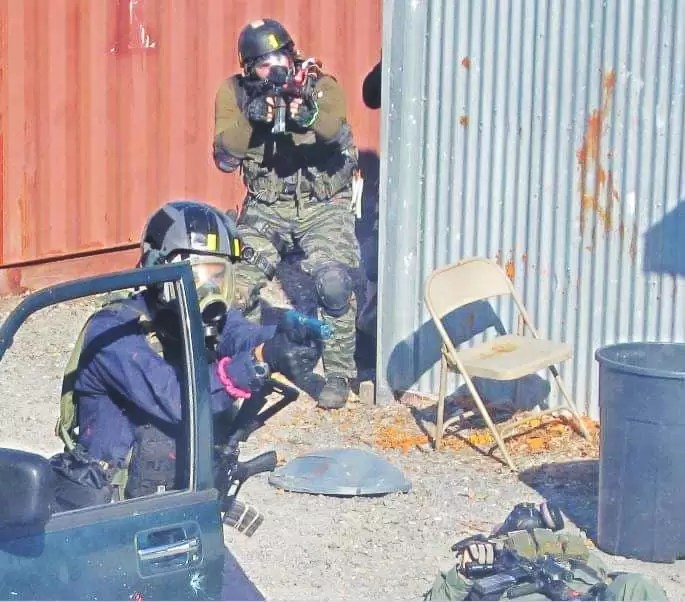

In Mid April, I attended a Greenline Tactical NVG Shoothouse class at the Alliance PD facility in Ohio. It was almost two years after I had been there for my last shoothouse class, where I had determined there was a need for an offset MRDS on my HK416 rifle setup. In the meantime, I had initially set the spare ACRO up on the Valhalla Tactical Rukh offset mount, but a few months later, Nick Booras finally came through with the ACRO saddle for the Elcan. Knowing this would be a perfect opportunity to test it out, I mounted it, took it to the range to zero, and got it all ready for class.

While there, in preparation for this article, I made it a point to utilize passive aiming through the ACRO as often as I could during my night vision runs through the shoothouse. For one, I wanted to make sure it worked like I intended, and that my theory held up in practice, knowing what I knew about passive aiming and tall mounts up to that point. Also, I wanted to make sure I had fresh feedback to substantiate what was originally meant to be an Elcan review before it evolved into this thesis, so that I could actually talk about using it as it’s configured rather than just why I liked what I spent my money on like every other review in the world. That being said…

This was my first time using the passive aiming technique, and I was surprised to find that it was both easy, and thoughtless. It felt like cheating, and I’m sure the height over bore had a lot to do with it. Seated atop the Elcan, the ACRO was tall enough and forward enough to clear my night vision, and the reticle came right up into my field of view whenever I brought my weapon up from a low ready depressed muzzle to address targets. There was no awkward pause trying to find the dot where I’d be attempting to line the weapon up in front of my night vision, not unlike some may experience handling a pistol equipped with an MRDS for the first time. It was just there, where it needed to be, when I needed it, with a plain old chin weld on a fully collapsed stock.

The brightness setting on the ACRO had to be turned down from its typical daylight bright setting, to avoid a bright blooming dot with a halo under night vision. I kicked it down to the point where you couldn’t see the dot with the naked eye, but under NV it looked like you’d normally expect an Aimpoint dot to look like. Because it worked so seamlessly, I was able to focus entirely on my footwork, muzzle & target awareness, and marksmanship, without having to worry about finding the dot.

It wasn’t just under night vision that I got to take my Elcan setup for a test drive. We’d also done dry runs in the house before sunset, and at least one white light run after sundown. So there were plenty of opportunities to use the optics package in all of the scenarios that inspired it to begin with. Using the ACRO in CQB during daylight was just as easy and intuitive as it was passively under night vision. The chin weld wasn’t remotely uncomfortable, despite having come up in the era of optics + cheek weld being King. With the Elcan SpecterDR sitting on 4x, there was even a point where I got to use it in the shoothouse to PID a target.

At one point, I was in the assaulter position getting ready to take a room. The breacher stepped up and opened the door, and I performed a threshold assessment of the room from the doorway. It was a corner-fed room, and straight ahead from the door along the short wall was a target. But it was a weird target. Up to this point, this specific target had been used as a no-shoot target throughout the house. But these were also modular targets where the hands could be changed with different pictures showing them holding weapons, other dangerous objects, innocuous items, or nothing at all.

This time, the girl in the target was holding… something. We couldn’t tell what it was though. Maybe because it was dusk and the lighting was weird and the target was reflecting swamp gas off a weather balloon, I don’t know. I touched it with white light from my Modlite PLHV2, and because of washout I still couldn’t tell what she was holding, and neither yet could my breacher. Then I remembered, oh yeah, I planned ahead for this. I dropped my head down from chin weld to cheek weld in order to look through the Elcan, and the 4x magnification gave me everything I needed to obtain PID proper. The target was in fact holding a gun, just at a very nonthreatening, awkward angle that made it hard to tell.

We took precautions this time after several of us tagged a previous bad guy target reconfigured as a no-shoot holding a gun shaped flashlight, so we wanted to be careful this time. Once we had PID, we plugged the target and moved onto the next problem. By this point, I was very pleased; the optics package I came up with worked exactly as I had planned for. Success!

All in all, objectively speaking, what do I get out of it personally? My tall mount has magnification built into it, and puts an MRDS right where it has to be for quick acquisition in CQB, clearing rail-mounted accessories (though with the MAWL this isn’t really a problem), use with a gas mask, and passive aiming, all while keeping the rifle held upright. It provides the same magnification as an ACOG for PID and addressing targets further out, but with better eye relief, and a better reticle that’s etched into the glass and will therefore always be there without having to worry about getting knocked loose inside the optic like a wireframe reticle could. Meanwhile, it takes up less space and balances the weight, but still weighs less than a Vortex Razor HD Gen II 1-6x + mount and MRDS. In a worst-case scenario, the ARMS levers allow me to quickly detach and stow the optic so I can deploy my backup irons and drive on. For a total package on a suppressed short-barreled rifle configured for both daylight and night vision use, it has everything I need for either setting and does its job extremely well.

We’ve reached the end, folks. Thus concludes my “review” of the Elcan SpecterDR 1-4x, why I picked it, and why I mounted the P1 ACRO on top of it the way I did. I have described to you the purpose and function of each component that went into it, the problems the optics package needed to solve, and the why and how we arrived at our current practices that informed its configuration, even as those practices come and go and come back again.

I’d like to thank the following friends for assisting me in this endeavor: Raymond Pembrose, Ryan Davis, Jim Carter, Chad Mercer, Tanner Beilue, Don Edwards, Sam Houston, Glen Armand, Nick Booras, Eric Burt, John Enloe, Jon Dufresne, Frank Plumb, Chuck Pressburg, and Augee Kim. I’d also like to thank Stickman, Matt Robertson over at Everyday Marksman, and everybody else on the internet whose pictures I used for the purposes of this article. I pulled so many pictures from Google Image search results that came from websites and forums and social media that I couldn’t begin to remember every single source. Just know that even if I didn’t name you personally, you have my gratitude regardless.

This was a labor-intensive but fun project, and I was happy to put the work in collecting and combining the pictures to make the diagrams while recalling all the lessons and details I’d picked up over the years, and organizing it in a way that consistently flowed from start to finish. I hope you found this helpful, and that you hold onto it as reference material going forward that you can look back on next time someone’s talking nonsense on the internet, or to help you and your friends figure out which optic configuration works best for you and your requirements; mine isn’t the end all be all, and it might not be what your rifle needs, but at the very least, hopefully, you’re more informed on how to approach the matter and what to take into consideration in the process.

Stay in this L.A.N.E.

FW